Russell Chatham: Moods of the American West

April 15, 2020

SCA Articles

SCA Articles

No man is one-dimensional, but very few people are quite as multi-dimensional or multi-talented as Russell Chatham.

It would be very easy – and so much fun – to write about Russell Chatham as a Rabelaisian voluptuary, the kind of man who wakes up every morning in a California-king-sized bed surrounded by empty bottles of Chateau Haut-Brion and empty-minded cheerleaders and with only a dim memory of where or even who he is. And while it might not be an entirely untrue portrait from an earlier time, it would be a little like describing J. M. W. Turner as the guy who did all those erotic drawings. Uh, well yeah, he did, but in his spare time Turner also dashed off some of the most magnificent and innovative landscapes and seascapes of the 19th century. Or any other century.

That Rabelaisian image owes its existence to some very wild and wooly articles about hunting and fishing written by Chatham during his salad days back in the ’70s. He is not the first man who has had to make a choice between two mutually exclusive passions (in his case, a naked woman with a green parrot on her shoulder and a once-in-a-lifetime meal of wild duck), but he is the first I know of to have written about balancing memory and regret quite so frankly. At the time, he ruffled quite a few feathers (not the parrot’s) with that story, and helped shape a legend for himself, but like all legends, it is only a small part of the truth. It’s like John Ford’s movie, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: “This is the West, Sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” It’s tempting, but the truth is much more interesting.

In an interview with the Bloomsbury Review, Chatham once said: “All genuine art grows outward from the heart, and is a matter of sensations. Art inspired mainly by the intellect may induce awe, excitement or even laughter, but never tears, and there is no great art without tears.”

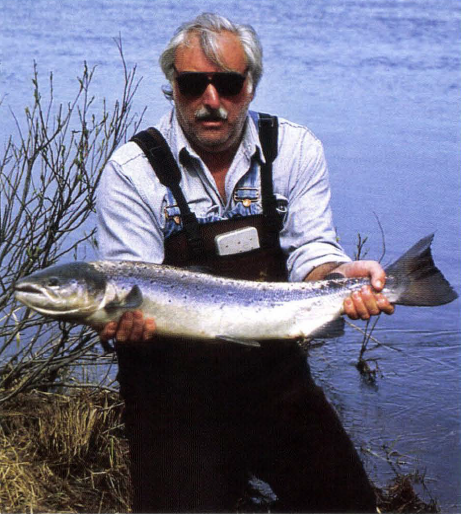

By itself, that statement goes a long way to defining Russell Chatham, the artist. The problem is there are many Russell Chathams. No man is one-dimensional, but very few people are quite as multi-dimensional or multi-talented as he is. Acclaimed painter; one of the world’s greatest and last living off-set lithographers; first-class writer; restaurateur; founder and editor and publisher of Clark City Press, which produced some of the most beautiful books of the late 20th century; one of the three best fly fishermen in the world today, according to both his friend William Randolph Hearst III and Chatham himself (Chatham caught the world record striped bass on a fly in 1966 and has by his own reckoning caught more striped bass and anadromous fishes than anyone alive today); hunter; gourmet; gourmand; drinker; pauper; millionaire; pauper again; lover of nature; lover of life; feckless wild man; devoted friend; constantly concerned parent…but out of all this, two things come into focus.

“I started painting when I was seven, and I started fishing when I was ten with grown-ups who really knew what they were doing,” he told me as we ate oysters and drank wine outside in the sun overlooking Tomales Bay. What remained unspoken was what I found later in Silent Seasons, an anthology of fishing stories published by his Clark City Press, which includes his own stories and others by Thomas McGuane, William Hjortsberg, Harmon Henkin, Jack Curtis, Charles Waterman and Jim Harrison. In his introduction, Chatham writes:

“Some of us went quite crazy over fishing at a pretty tender age. I think those like myself were at first seeking a kind of refuge away from the erratic and sometimes frightening behavior of our young peers. Or, in other cases, our parents.”

It doesn’t take much imagination to hear the tears resonating behind those words, but if the past can drive a child to refuge and leave phantoms that linger long into adult life, the past can also shape the child in ways that coruscate, ways that resonate with the brightest and most knowledgeable among us.

The list of rich and famous, the high and mighty who collect Chatham’s work, would fill an entire page, but just for fun, a few: Tom Brokaw; authors Richard Ford, Tom McGuane, Jim Harrison, Peter Matthiessen and the late enfant terrible Hunter S. Thompson; the original (and now deceased) Hollywood Madam, Alex Adams (don’t ask); William Randolph Hearst III; Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen; Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard; most of Hollywood, including Jack Nicholson, Harrison Ford, Warren Beatty, Sean Connery, Jamie Lee Curtis, Robert Redford, Jeff Bridges…the neon names go on and on, dripping gold and diamonds and gossip.

Forget those people. The name that should make you sit up and take notice is the late Robert Hughes.

I have zero use for art critics. At their worst they are as dangerous to art as war, being for the most part arrogant twits who make their livings off the doubts and insecurities of people with more money than taste or judgment. Most of them tend to promote their own particular artists for their own particular purposes that frequently have little or nothing to do with art. (As Robert Hughes himself once wrote: “The new job of art is to [hang] on the wall and get more expensive,” as damning and accurate a comment as I have ever heard.) But writer, producer and (shudder) art critic, Robert Hughes, was the exception that proves my own rule.

Highly educated, hard-nosed and hard-living, controversial, he was the art critic for Time magazine, and produced several television specials, including one on art called The Shock of the New. Most importantly, I sometimes agreed with what he had to say, so clearly, he was a man of staggering genius and exquisite taste. Art critic Robert Hughes collected Chatham’s work.

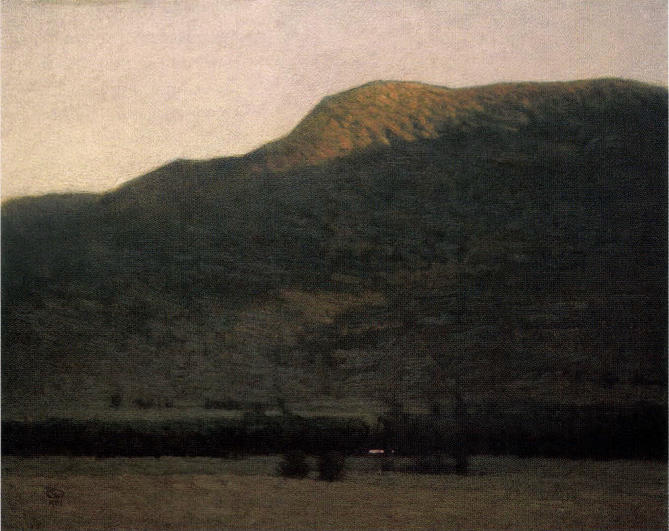

Russell Chatham’s painting reflects an extraordinary degree of subtlety, sophistication and tremendous discipline. In a national magazine article about the artist Edward S. Curtis, Chatham describes Curtis: “As a painter and draftsman as well as a photographer, he attained art’s greatest goal: he made his process invisible.”

Chatham might just as well be writing about himself. He works simultaneously on a great number of paintings in varying stages of progress. When I visited him in his studio on Point Reyes cape in northern California, he took a small painting I would have happily purchased as it was and proceeded to horrify me by smearing paint over it and then wiping everything off. The result was an infinitely subtle change of hue, one that would have been indiscernible if I hadn’t witnessed it.

He then leaned the painting back against the wall, where it will remain for days until the oils harden enough for him to do the same thing again and again. He will repeat this process for a year or more to create an illusion of depth, which is a signature style of Chatham’s.

His reliance on color (as well as focus, overlapping, diminishing scale and so on) as opposed to diagonal lines, tricks the eye into seeing an optical illusion of depth, an illusion that delights endlessly, but unfortunately only with the real thing, not with reproductions. The more subtle the painting the harder it is to reproduce, and Chatham’s use of atmospheric perspective (I believe it was invented by Velasquez) is a style that does not reproduce well with modern reproduction techniques, which is in part why he trained himself to be such an accomplished lithographer, another art form almost as painstaking and time-consuming as his oils.

Chatham’s grandfather was Gottardo Piazzoni, one of the most acclaimed tonalists of northern California’s golden era from the turn of the century to his death in 1945. Where other children are told to go outside and play in the traffic, Russell was told to go outside and paint, and by his own admission he was so heavily influenced by his grandfather’s art and reputation that for many years everything he painted looked like Piazzoni’s art, so that working our way into the past through Piazzoni ‘s own influences, we may say Chatham was influenced by the Barbizon school and the echoes of Millet, Corot, Rousseau and others.

But while Chatham is also a tonalist like his grandfather, we can end the comparisons right there. Without getting all Art 101 on you, two of the chief characteristics of the Barbizon school were “realism” (as opposed to “idealism”), and the practice of painting outdoors, on site (en plein air). Today, those landscape artists who do not work en plein air take voluminous photographs and work in their studios from those, some actually projecting a photograph onto the canvas and, in effect, painting by numbers. Russell Chatham does neither.

“A fisherman looks at one percent of the river because the other ninety-nine percent doesn’t have fish. It’s the same thing painting a landscape. I dismiss ninety-nine percent and focus on a pinpoint in space and time. Then I go back to the studio and paint from memory. It’s sort of like taking a photograph with my brain and letting it out through my fingertips, so there is a transformation of reality into an essence of place and time.”

Essence indeed: this is the essence of art; it’s also pretty much the essence of fishing, and I suspect that for Chatham there is not much distinction between those two. Consider his assessment, in his volume of autobiographical essays, The Angler’s Coast, of his fishing mentor and hero, the late Bill Schaadt:

“It [was] his overall sense of understanding, curiosity, deep love of the natural world, energetic effort and his style which set him so clearly apart from his contemporaries.” That could be Russell Chatham talking about Russell Chatham the fisherman, or it could be Russell Chatham talking about Russell Chatham the artist. Or both.

As a fisherman, Chatham reminds me very much of Norman Maclean’s description of his father: “…our father was a Presbyterian minister and a fly fisherman who tied his own flies and taught others. He told us about Christ’s disciples being fishermen, and we were left to assume, as my brother and I did, that all first-class fishermen on the Sea of Galilee were fly fishermen and that John, the favorite, was a dry-fly fisherman.”

When we first met, at a restaurant in Point Reyes Station, Chatham pulled out a number of reel cases and put them on the table. I had done my homework, and I knew he was a serious world-class fisherman, but I also knew his paintings were collected by some of the richest and most famous men in the world, and my heart sank. I thought he might turn out to be one of those phonies for whom the expense of the toy is part of the aesthetic experience, the kind who think of fly fishing as being the height of patrician elegance and refinement, the piscatorial equivalent of the Social Register, or a debutante ball.

I needn’t have worried. All of those reels were older than he or I, and in just about as bad shape. To someone of my decidedly amateur status (rank amateur, third class) as a fisherman, the reels had a decidedly utilitarian look – not just utilitarian, but working class, blue collar, much the worse for wear, with none of the refined and feline elegance we associate with high-end reels today. Raw aluminum, no fashionable gleaming oxidation, bent and battered as a boxer’s nose, they looked as if they should be on display in a dusty, backcountry fly-fishing museum.

If you look closely at the some of the photographs of Chatham in his Dark Waters anthology (fishing with the late Richard Brautigan, with Tom McGuane, Guy de la Valdene, Jim Harrison, others), you’ll see some of those reels.

Chatham is so far advanced as a fisherman that his snobbery, if you will, has nothing to do with externals, Harris tweed, Hardy reels, split cane bamboo. Instead, his snobbery is restricted to the aesthetics of ability and enthusiasm, and love of the experience. If you don’t have those, you’re no better than the slobs, literally, he describes in Salmon on the Fly…or on the Run:

“A labyrinth of well-worn trails strewn with trash led down to the river. Once there you faced an unfathomable amount of additional garbage: discarded lure packages, cardboard bait containers, food wrappers, rags, beer and soda-pop cans, and an altogether dangerous amount of snarled monofilament. Covering it all like the finishing touch on a bad practical joke, or the icing on the cake, was a vast, matted layer of salmon eggs – discarded bait – combined with white powdered borax. The borax is used to preserve roe, giving it a tough skin so it stays on the hook. When dropped on the ground (an apparently mandatory detail), it lends the scene an ambience only to be otherwise found in the most ill-kept Laundromats of east Los Angeles.”

For Chatham, fishing is not about the equipment or even the fish, but about the aesthetics of the experience, experience that can only be purchased with years and knowledge and a great deal of love.

The moment you purchase a Chatham painting and hang it on the wall, it becomes a reflection, for better or worse, of the space around it. How often have you gone into a museum and admired a painting, and then turned to the person with you and said, “And, my God, look at that frame!” A spectacularly sculpted, gold-rubbed frame is a legitimate work of art in its own light. The problem is, when two works of art are juxtaposed as closely as a painting and its frame, neither can be fully appreciated.

Chatham is one of the few artists working today who seems to understand this. (His comment about seeing some of J. M. W. Turner’s masterpieces unframed in London: “Relieved from imprisonment within seven hundred pounds of gold filigree, the works appeared almost buoyant.”) He designs his own frames and has them made to his specifications for each painting.

First, a massively strong laminated structure is created in scale to the specific painting. The laminate is then covered with a surface veneer of raw walnut, which Chatham then “washes” with oil pigment mixed to compliment the tone of the painting. Some frames are also enhanced with a very thin border of gold. The result is a protective work of art that enhances without distracting from the work of art you should be looking at.

Chatham is predominately labeled a Western landscape artist, and though he has also painted animals (winter scenes of elk; birds; cattle; a hauntingly evocative painting of Betsy Huntington and her dogs for the cover of Stephen Bodio’s magnificent memoir, Querencia), it is landscapes one automatically associates with his name. Many are large in scale, 4×5 or 6×8 feet, some even larger, and in the relatively small space of his studio, they lean against the walls in stacks, in various stages of completion. One, perhaps 5×6 feet, still showed some of the original lines he starts with to provide an outline of the “pinpoint in time and space.” I commented on the newness of it.

“Actually, I’ve been working on that for about a year, but I’m probably another year away from completing it. It’s giving me fits because I haven’t yet figured out how to get where I want to go. That’s why it’s there. I look at it every day so that one day I’ll come in and know automatically how to finish it.”

It’s one of a set of four commissioned by a dot-com prince who is designing his house around the paintings, a man who is willing to wait for the artist’s mental photograph to come out through the fingertips. It gives you an idea of just how revered Russell Chatham’s work is.