It’s All in the Details

January 8, 2021

SCA Articles

SCA Articles

Montanan Fred Boyer translates his most memorable sporting experiences into monumental sculptures of wild animals.

For Fred Boyer, there is no separation between living a rich outdoor sporting life that has little to do with money and celebrating it in a way so that we, the viewers, literally feel the texture of what he’s expressing in our hands. If Boyer’s not away on safari somewhere in Africa or Asia, he might be fishing the Montana streams near his porch that Norman Maclean made legendary in his novella “A River Runs Through It.”

“What you see in Fred Boyer’s artwork is a close attention to different experiences that he knows intimately,” says Walter Matia, a fellow award-winning wildlife sculptor whose collectors include T. Boone Pickens and whose art can be found today in several major museums. “I have profound envy for Fred. When you are dealing in the story of hunting and fishing as your genre, having actually lived the adventures you’re communicating, it does out in the work.”

Not bad for a humble, often soft-spoken man who hails from the rough-and-tumble, former copper smelting town of Anaconda (where he still lives), who spent several youthful summers working as a Forest Service smokejumper battling western wildfires, and who then became a beloved high school art teacher before he finally figured out what he wanted to do with the rest of his days. Astoundingly, that was 31 years ago.

For Boyer, retirement has never figured into the grand plan, certainly not when a guy can still carry a 60-pound backpack, scale a ridgeline a dozen miles from the nearest road, and bury one’s hands into the pliable mass of modeling clay.

When I finally caught up with Boyer – yes, it took some doing – he was packing his bags again, heading off as he does every spring and early summer to guide bear hunts in southeast Alaska. Up north, around Sitka where he once taught drawing classes, he is revered for having an uncanny ability to locate bruins on the ABC islands. Many of the massive, salmon-filled brown bears top 1,000 pounds and measure more than 10 feet from snout to hindquarters. When one rises three feet in front of you on hind legs to whiff-scent your presence, it’s a pose one never forgets, Boyer says.

There is no such thing as catch-and-release bear hunting and 99 percent of his encounters Boyer chalks up to valuable non-lethal field research, in which clients too are encouraged to study the nuances of individual animals, being discriminating before they get in position for a shot.

When they’re successful, Boyer the bear scout turns into Boyer the anatomist who by readying hides for shipment to a taxidermist uses the opportunity to understand musculature and physiology in ways that other contemporary animal sculptors often do not.

Boyer’s Alaska season, however, is merely a prelude for the one he craves most – autumn in western Montana where memories go back a half-century.

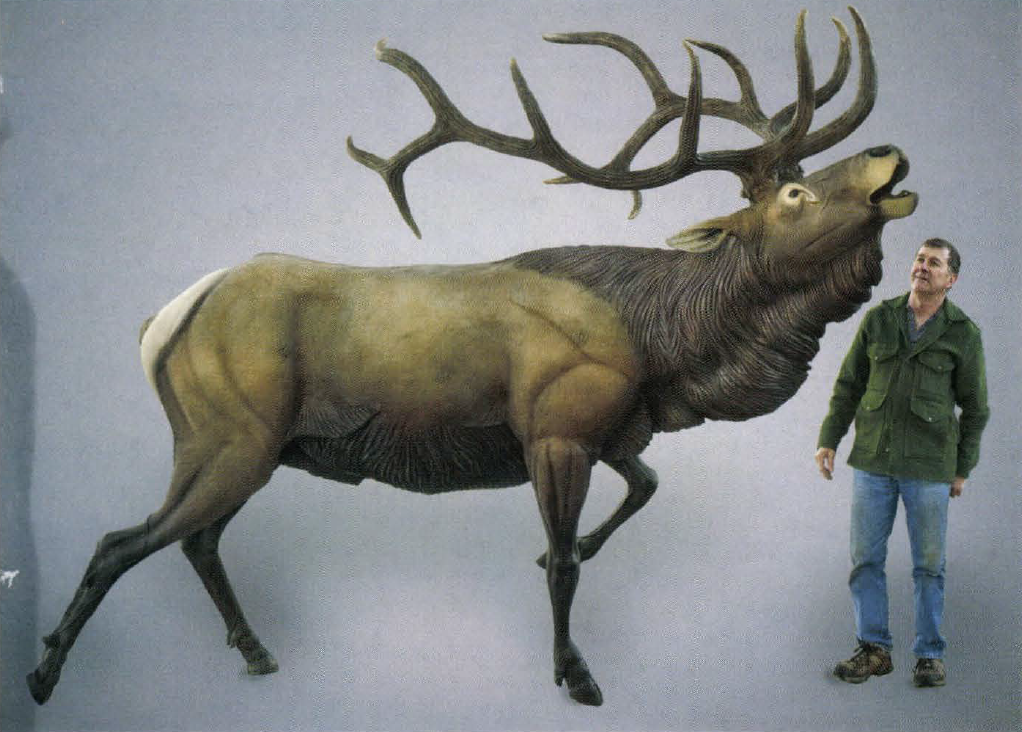

On this day, the 2013 Safari Club International Artist of the Year was wrestling in his studio with a subject even bigger than a coastal brown bear – a gargantuan Rocky Mountain elk – that weighs more than a ton. Titled Autumn Royalty, the larger-than-life-sized bull wapiti, its antlers tilted heroically skyward and mouth agape in full bugle, is one of Boyer’s bronze monuments.

Truth be told, he says, the actual seven-by-seven, 400-plus Boone & Crockett qualifier that inspired his sculpture doesn’t reside as a stuffed head in someone’s trophy room. The monarch still lives, so far as he knows, inhabiting the Big Hole River valley and its many draws in western Montana. The fact that the bull is out there means that he also maintains a haunting, elusive presence in Boyer’s imagination.

“The rack on that bull is modeled after a real shed antler found in the Big Hole, but, of course, I won’t tell you where,” Boyer says. “All that I was able to get my hands on was just the one side. I would love to see the whole spread moving through the mountains on the head of the live animal.”

Boyer’s work is popular among sportsmen because he captures the mystical allure that keeps summoning us back to wild country. For Boyer and his good sculptor friend Robert Duerloo, only 126 road miles separates them. Each has a strong affinity for big game, though their interpretation of the great beast differs.

“He is a true outdoorsman, a hard charger,” says Duerloo. “And when it comes to knowing his subjects well, Fred walks the walk.

Even on his African safari, Boyer was hands-on, helping to remove the capes and skins so he could examine the musculature of both predators and prey.

“We both appreciate the animal form, but have totally different styles,” Duerloo notes. “Fred knows what his clients want. At Safari Club, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and Wild Sheep Foundation events, those collectors are seeking artwork with a lot of detail.”

Boyer’s realistic sculptures, identifiable for their colorful, hand-painted patinas, are known to collectors of sporting art around the world, each one inspired by personal encounters Boyer has had with big game animals and birds. Collectors of his art include major league baseball hall of famer Wade Boggs, former President George W. Bush and the late four-star General H. Norman “the Bear” Schwarzkopf.

For those seeking a fully informed verdict on the quality of his work, there’s probably no one more enthusiastic than retired Montana District Court Judge C.B. McNeil, who along with his wife JoAnn have amassed the largest private collection of Boyer sculptures.

The judge recalls a conversation he had with Montana game warden Louis Kis, a talented wildlife photographer, as they stood before some of Boyer’s sculptures at an art show.

“I can’t remember exactly what the animals were that we were looking at. Probably an elk or a bear or bighorn, but I asked Louis what he thought of Fred’s latest work. He coyly said, ‘Pretty good.’ And I responded that I think he’s every bit as good working in bronze as Charlie Russell was. And then Louis, having paused for a moment, corrected me and said, ‘No, Fred is better. ‘”

In the state that Charles M. Russell adopted as his home and set as the venue for so many sporting “predicament scenes,” there could be no better validation.

“Being from Montana, you can’t help but be influenced by Russell,” Boyer says. “Most of his sculptures were done as research material. He used working models to see how light and shadow worked. A lot of his larger, more ambitious pieces were done quickly but they’re impressive compositions.”

While McNeil says that he has profound respect for impressionistic wildlife sculptors who can insinuate anatomical detail in their subjects, he is drawn to Boyer’s work because he painstakingly conveys the actual look and feel of mammals and birds.

“I’ve seen him spend weeks to get the feather patterns for a goose right or the profile of a sheep curl. When you’re standing six feet away, you just don’t see it but step closer and you appreciate the attention that Fred brings,” McNeil explains.

“Many contemporary sculptors have loose, flowing styles but they lack the hands-on knowledge of the animal that Fred possesses. Detail is his way of recognizing and honoring the beauty of an animal, celebrating the things that set it apart from other species.”

Before he earned his law degree, McNeil received an undergraduate degree in metallurgical engineering. He appreciates the designs of Boyer’s maquettes and marvels at the translations of several pieces to monumental dimensions.

Autumn Royalty was first born as a maquette, another in Boyer’s big game series that has attracted art collectors from around the world. Those works are created at quarter scale of the original animal and then, using the sculptural process called “pointing up,” are grown to 1.25 life-sized.

Five castings of Boyer’s acclaimed Alaskan Yukon moose monument, Monarch of the Stikine, today adorn public venues in the U.S. and Canada. One of the nine-foot-tall bronzes greets visitors at Cabela’s in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Wild Wings, which has long represented his work, also carries a small bronze edition.

Boyer is philosophical about the awe he holds for moose and elk that inspired the monuments.

“You’ve got a massive animal with a set of antlers that stretches several feet across. He’s in command of his surroundings; he’s earned his place among competitors vying for mates; and he can be as loud as he wants to be,” he says. “But then again, he’s usually not, and that has made him a survivor.

“In a second he’s on the move and trying to be discreet, being as stealthy as he needs to be. He can slip through the timber without making a sound. I admire him because he’s just out there trying to make a living and stay alive. He doesn’t want you to know he’s there, but you can feel it.”

All of Boyer’s monuments are complicated feats of production. He uses Valley Bronze, the same full-service foundry in Joseph, Oregon, that delivered most of the decorative bronze work for the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C.

In 2014 Boyer’s small tabletop portrayal of mountain goats, titled Three Wise Men, sold for $11,500 at the SCI auction. As an indication of his appeal, Boyer years ago produced an elk piece in a special 100-run miniature edition for the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, and it sold out.

The same coveted status applies to his mountain sheep pieces, yet it’s actually a funny thing about Boyer and sheep. He has hunted Dall sheep in the sub-Arctic north and taken big rams, but in 44 years of putting in for a sheep tag in Montana, he’s never drawn one.

“I’ve been on a lot of sheep hunts here with friends for several decades and helped them pack out animals. I was with a friend who killed a massive ram with his bow, but I’m still waiting for my chance. It may never come.”

Boyer doesn’t mind. In some spur ranges of the northern Rockies, sheep have disappeared, and Boyer would rather that his sculptures raise awareness and, where possible, bolster conservation efforts spearheaded by the Wild Sheep Foundation. At several sporting and art events, Boyer’s pieces have won best of show honors and people’s choice awards.

Painter Trevor Swanson met Boyer on stage the same night that he received artist of the year honors from the Foundation for Wild Sheep, and Boyer earned rarefied distinction as “a living legend.” Ever since they’ve been comparing notes, sharing critiques and arranged to have booths next to each other at SCI’s annual exhibition.

“Fred doesn’t do anything strictly to be marketable,” says Swanson. “He has a deep sense of connection to his subjects. He has a sensitive touch when it comes to game birds, but to be honest, I’ve always gravitated toward his antlered animals, his elk and mule deer.

“Whether it’s a small piece or a monument, he captures the majesty of the animal. There’s something about the pose, the way his animals hold themselves, that make you want to touch his sculptures, feel the texture, and want to live in the moment that’s being portrayed.”

“I want to depict grandeur and grace,” says Boyer. “When I think about how strong and unique these creatures are, how they’ve been extensions of wild country going back thousands upon thousands of years, I don’t know what to say. That’s why I’m an artist. I don’t have a personal favorite. Very likely, if we’re ever out there together and looking at a moose or bear or goat or elk, I am likely to think: Isn’t that one the coolest animal there is?