The Most Ambitious Two-Dimensional Wildlife Artwork in History

June 4, 2020

SCA Articles

SCA Articles

Brian Jarvi’s magnum opus is touted as one of the most inspiring wildlife paintings ever.

It is an extraordinary thing in modern fine art to witness a spontaneous standing ovation—even rarer is a rousing reception that involves a single painting of wildlife.

Yet in autumn 2017, deep within the lake country of northern Minnesota, that’s exactly what happened when Brian Jarvi unveiled his epic African Menagerie: An Inquisition.

Some 700 people filling the Reif Center for the Performing Arts in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, rose to their feet and roared wildly after a stage curtain was pulled. Glowing in the klieg lights was Jarvi’s long-awaited magnum opus.

Those who encountered it that night, including this writer, knew instantly it is an important scene for the ages.

As readers of Sporting Classics are keenly aware, Jarvi is lauded for his large African action scenes involving charging elephants and predator-prey encounters typically featuring lions and wildebeest or Cape buffalo.

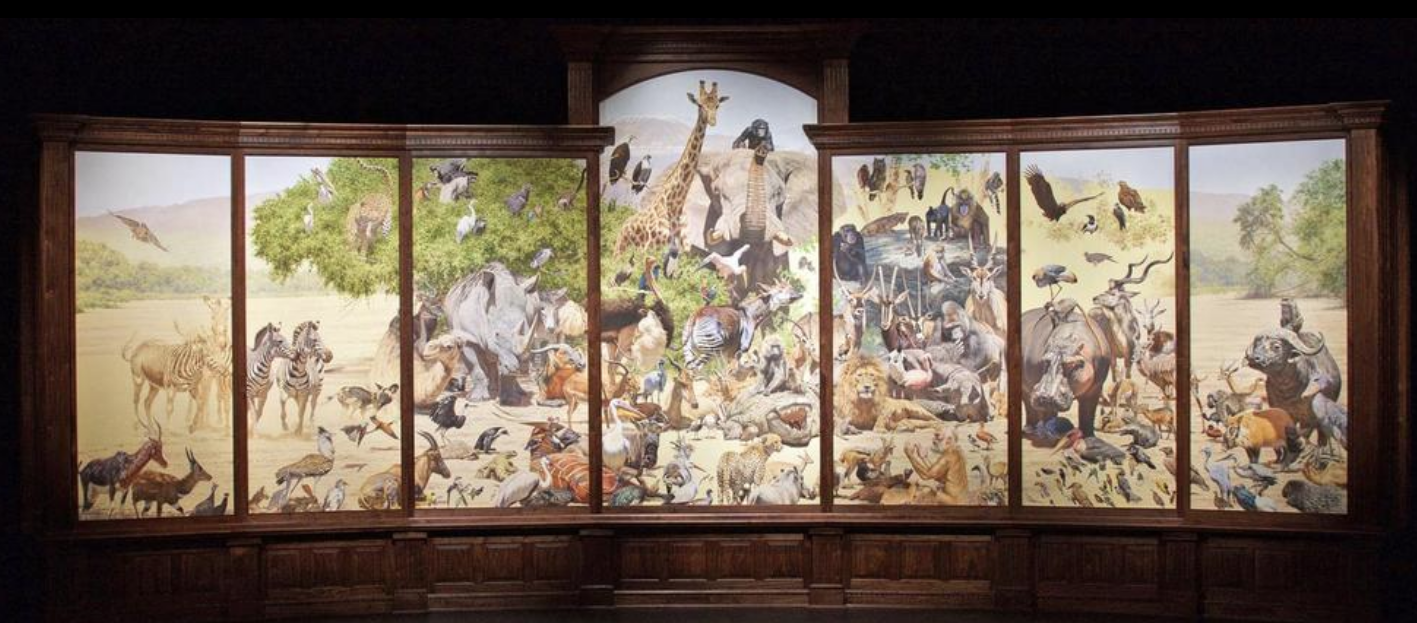

African Menagerie, however, is no mere traditional work on canvas; it’s best described as a spellbinding visual monument. Measuring 28 feet across, interconnected by seven panels and towering 1½ stories high at its tallest point (the apex coinciding appropriately with Jarvi’s portrayal of the summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro), it’s one of the most ambitious two-dimensional wildlife artworks completed in history—both in scale and number of species it covers.

No actual African safari would come close to delivering the variety of species in Menagerie, a project that took Jarvi more than 14 months to paint. In all, some 208 African icons and lesser-known inhabitants of the savanna, desert, mountains and equatorial jungle converge in a breathtaking mosaic.

The Big Five plus dozens of recognizable other animals are prominently featured, speaking to Jarvi’s affinity and devoted following in the hunting community. Still, it’s the numerous creatures, large and small flanking the familiar, that awaken us to what’s at stake during this century when wildlife across so much of the globe is in decline. Beauty can be a powerful motivator.

“With African Menagerie, Brian Jarvi not only showcases his talent and skill to render his subjects realistically, but he inspires us to stop and take notice,” says renowned Canadian artist Robert Bateman. It is Bateman, along with the late Bob Kuhn, David Shepherd, Simon Combes and others, who set the standard for contemporary depictions of African game. Jarvi is one of the stars of the next generation.

“We are at a critical juncture in human history where we hold the future of the natural world in our hands,” says Bateman, who praises the contributions hunters have made to conservation. “Without conscientious thinking about how we can steward iconic species, starting with preserving their habitats, they will be lost.”

The challenge is remarkably similar to the one that great American and Canadian painters confronted at the end of the 19th century when wild ungulates ranging from bison to elk and predators such as bears, cougars and wolves were devastated in many corners of the continent.

Painters such as Thomas Moran, Albert Bierstadt, Charles M. Russell and Joseph Henry Sharp provided visual ammunition to Theodore Roosevelt, William Hornaday and others in building the ranks of the Boone & Crockett Club, drafting principles for the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, and protecting public lands to serve as crucial reservoirs of habitat.

The plight of African species has weighed heavy on Jarvi’s mind, and the idea behind Menagerie had been percolating for three decades. Complemented by dozens of finished studies, the giant painting was then on a national museum tour. Curators say it is like an entire art collection, earning comparisons to the historic frescos painted by Italian and Flemish masters of the Renaissance.

“I’ve never seen any other contemporary piece like it,” says David Wagner, curator of the museum exhibition. “African Menagerie makes any room it inhabits live larger because it has an almost interactive quality. You don’t want to take a photograph of it. You want to take a photograph and put yourself in it.”

In winter 2019, the painting made a stop at the Minnesota capitol building rotunda after appearing at the annual Safari Club International convention in Reno, Nevada.

“Menagerie is so novel and its range of species so visually accessible and intriguing in a variety of ways, that I see it not only as Jarvi’s artistic pièce de résistance, but also the kind of standalone piece that would be a capstone of any collection,” Wagner notes.

On top of Menagerie’s museum tour, the respected international art publisher Rizzoli published a book about Jarvi. Special collector editions of the volume were produced featuring true limited-edition etchings created by Jarvi and suitable for framing.

Jarvi’s rise to prominence as a contemporary wildlife artist represents a vast departure from his trajectory in the early to mid-1980s. At the time, he was among a noteworthy group of Minnesota painters who distinguished themselves with waterfowl subjects. His close Minnesota friends, Daniel Smith and Bruce Miller, each won the Federal Duck Stamp, and Jarvi himself had a painting appear on the Minnesota Duck Stamp.

Yet wanting more, the threesome sought to break away from the cliché of that genre and establish reputations as fine artists in their own right. For Jarvi, a turning point was going on safari to Africa over 30 years ago, the first of 13 research missions he’s taken.

“You can’t imagine how rare it is for an American to make paintings that leave you feeling as if you’re coming home,” says Zimbabwean-American fine art gallery owner Ross Parker. “Jarvi has absorbed Africa via osmosis, soaked in it at the soul level, and is able to articulate it, as if it were always innate to his being.”

“The excitement lies in transferring situations I have witnessed on safari onto canvas,” Jarvi explains. “The tremendous diversity, the sheer numbers, and the often-sobering confrontations of wildlife have spawned more ideas than I can ever hope to translate, yet they all converge in Menagerie.”

According to Bruce Miller, after painting tightly and aspiring to render a photographic-like painting, it’s difficult to change into a looser style that is competent and unmistakably your own. Jarvi continued to evolve, forcing fine art critics to sit up and take notice. Even today, Miller is somewhat perplexed that Jarvi isn’t better known as an American painter—not as an American wildlife artist, but as a fine artist who just happens to paint animals.

“If he’s not the best wildlife artist in the world, then he ranks within the top three, and I don’t know who the other two are,” Miller notes. “The caliber of animal painter he is shows how damned fine a painter he is in general.”

Among contemporary painters of African wildlife, few have as much name recognition as John Banovich. Renowned for his portrayals of African species, he commands rock-star appeal among sportsmen and women, especially those art collectors who regularly embark upon hunting and photographic safaris.

Between them, Jarvi and Banovich have won several wildlife artist of the year honors from prominent organizations, and their pieces have commanded six figures at auction. They are admirers of one another, not rivals.

“I’m a big fan of Brian’s work and always have been,” Banovich says. “We emerged in our careers around the same time. Brian captures the soul and character of Africa as good or better than anyone. The thing I admire most about him is that here he is, in the last third of his career, as I am, and he’s taken this unbelievably bold move to create something very few artists in living history have attempted to do on such a scale. I’m really blown away.”

Banovich said he and Jarvi are both heeding the call to make a difference by using art to stir people’s emotions. According to Jarvi and Banovich, if one is really dedicated to saving African species, then they cannot be anti-hunting because in many countries it is vital to local economics and shows that animal populations are worth more alive than dead. That’s crucial in the fight against black-market forces killing rhinos for their horns and elephants for their ivory tusks.

Wielding a paintbrush that sways massive numbers of people can be a potent tool.

“I think that we artists are compelled by our fascination with nature,” adds Banovich. “We’re not trying to tell the world how to think, but when you spend hours and weeks and months collectively in special places as we have, it is your hope that your art might stir the viewer.

“Africa is changing so rapidly. The fall of some of these ecosystems is happening on a scale I never could have imagined when I first set foot in them three decades ago. We are at the stage where it’s all hands on deck. No matter what your favorite organization working in Africa is, support it. No matter if your elected officials are Democrat or Republican, call and let them know that the survival of African species matters. The most important thing is that we stand up and take notice. This is where art comes in.”

African Menagerie is a celebration of life on earth. There are, after all, no African elephants or lions on Mars, no rhinos or Cape buffalo on Venus, no pink flamingos, leopards, hippos or gorillas on the moon. Our planet is a miraculous miracle. If a microbe were proved to exist on those neighboring orbs, it would be earth-shattering. Instead, higher lifeforms are present only here, each one the product of millions of years of temporal engineering. And once a species disappears, like the Dodo, it is gone forever.

In these times of social unrest, divisiveness and uncertainty, it’s sad to see how difficult it is for Americans to rally together and pay attention to the important things that unite us.

Jarvi reminds us that it can happen with an art project that seizes our attention with its dazzling beauty and originality, and then inspires us to count what’s in front of us and gasp at the thought that much of our living earthly treasure could be lost.

African Menagerie implores us: Let’s not let it happen.

“Art can serve as a powerful rallying cry to save the natural world,” says Bateman. “It’s important that we heed the message Brian Jarvi is delivering.”