Golden Light and Lavender Shadows

June 17, 2020

SCA Articles

SCA Articles

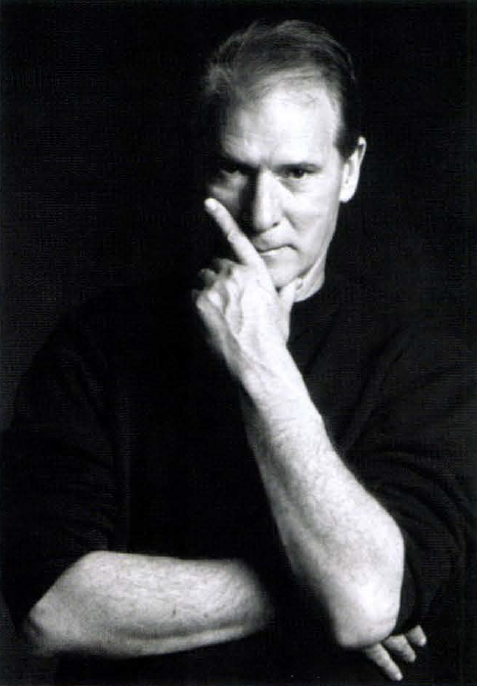

Charleston artist John Carroll Doyle was once offered an island for a painting, but he turned it down.

John Carroll Doyle crossed his last river in November 2014. He was my brother in the spirit if not in the flesh. The man had class, a soft-spoken gentleman with a keenly whetted sense of humor, a photographer, a philanthropist, philosopher, and storyteller, a wooden-boat-builder and a writer who penned his own obituary. But foremost he was a painter, a “Charleston Impressionist,” a southern coastal heir to Monet, Renoir, Van Gogh, Gauguin and every bit as good.

Extravagant praise, not casually tendered. If you love the roaring sea, brave fish and foolish fisherman, if you love the humble pleasures of shrimp crackling in low-tide creeks, a flounder in a cast net, a bucket of succulent oysters, you need to know the works of John Carroll Doyle.

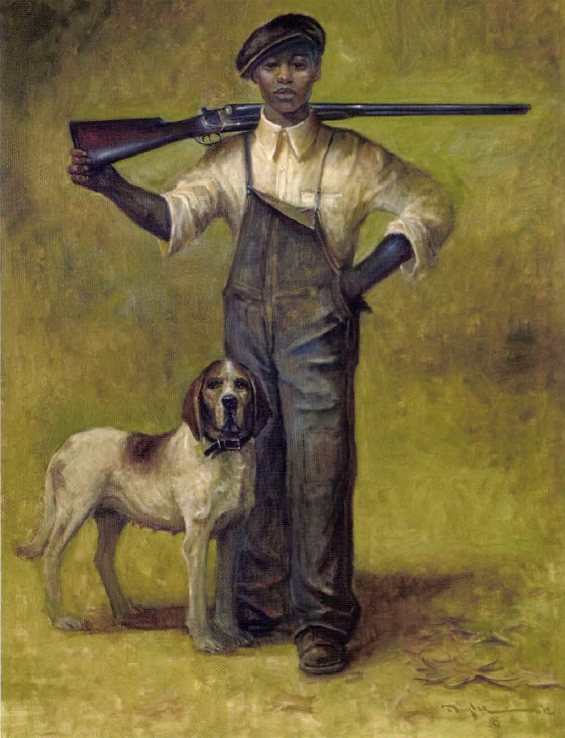

In the beginning, John Doyle painted your typical flowers in vases, fruits in baskets, still-life stuff very good but ditto boring. But oh, there were the women, stunning nudes indoors and out, whenever he could pay or hornswaggle a model, and like me he was partial to redheads. He painted Charleston street musicians, crap-shooters, card-sharks, flower vendors and plantation gundogs. But he made his fame and a small fortune painting bill fish and big-game fishing.

Born in downtown Charleston in 1942, John was only four when he began sketching on the margins of church bulletins he could not yet read. Happier days were spent knocking around the marina docks or on the banks of Colonial Lake in the city’s historic district. Colonial Lake is warm and shallow, perfect habitat for fatback mullet, silver acrobatic fish that jump at the slightest provocation. It was also where Charleston’s model boat hobbyists gathered to run their creations in mini-regattas.

“The child is father to the man,” the poet says. It may have taken 30 years, but one otherwise normal night in the late 1970s John was hooked over the bar at his favorite watering hole, Capt. Harry’s Blue Marlin in the market district, when the owner asked him to paint a marlin that looked like it was about to “jump off the canvas.”

John had painted yachts, shrimp boats, rowboats and sportfishing boats, but never a marlin.

“How much will you pay me for it?” the artist inquired.

“Two hundred dollars.”

Necessity being the mother of invention, John applied himself. Although he had seen billfish in the wild, unlike the redheads, none had obliged him with a pose. He studied photos, movies and taxidermy, encyclopedias and billfish ID charts. John got the job done, blew the money but learned a very valuable lesson.

“You can hang a painting in a gallery and somebody will breeze through and spend maybe five minutes looking at it. But hang it in a bar or restaurant, and a person will look at it for hours.”

Charleston was poised to become a major tourist destination with global media coverage, and John’s work was conveniently hanging in upscale bistros all over town. Luck or genius, you make the call.

“Damn, who painted that fish?”

“Johnny Doyle,” the barkeep would reply.

“You mean that guy who always sits on that stool over yonder? Wonder if he would paint me one?”

“I bet he would.”

Commissions followed commissions. In 1989 John painted the cover for Marlin Magazine to international acclaim. It caused a feeding frenzy. In a dozen years an original Doyle went from two hundred buck to ten grand.

Along with the Marlin cover, there were plans to market 300 signed and numbered prints and John needed help. Wendy Temple was editor for a local magazine and she ran into John frequently at the print shop they both used. She applied for the job and got it. John knew he had finally made big time, for an essay on copyright law was part of the application.

“John could paint a five-by-six-foot canvas in three days,” Wendy remembers. “He had such talent. It seemed that paintings just magically flowed from his brush.

“One day he showed me a photograph of a small tropical island in a turquoise sea. John told me that one of his collectors wanted a marlin painting so badly that he offered him an island if he would paint one for him! But for some reason John did not like this guy all that much, and even with an island as payment it was no sale.”

Heady times, but then a hurricane got in the way. Hugo hit Charleston later that year, roaring ashore as a Class Three, pushing a 20-foot surge. Tens of thousands bolted for higher ground, including Wendy Temple. But John stayed and rode out the storm. The wind peeled the roof off the studio and rain soaked him to the bone.

During the eye, he fled to his car across the street, no safer but a lot drier. His apartment was upstairs and most of his possessions were heavily damaged or utterly destroyed. The famous marlin painting somehow survived.

Fine print: From birth, during the struggle and the deluge, John Doyle was dyslexic. If he looked at a sentence, he would see the last word along with the first. If he looked at a paragraph, he’d see the whole cussed thing at once. He was a miserable student and liberally medicated himself with various intoxicants. He beat those demons and dyslexia too. Maybe he did not beat dyslexia, but he refused to accept it as a disability.

“I can see the finished work when I start it,” he told me once. “I bet there are a lot of painters who wish they could do that!”

A wild and gratifying ride, but no matter the success, John Carroll Doyle would still be Johnny Doyle to those who knew him best and from them he drew his spirit.

Ben Moise, retired game warden, raconteur, bird hunter and author remembers this incident. “Lukie Lucas and I were making a beer run and stopped by John’s little studio on Sullivan’s Island to visit. In the course of the conversation Doyle asked Lukie if he would like for him to paint a portrait of his Boykin spaniel. Lukie responded, ‘Doyle, you painting dogs now? I can still remember when you were dating them.'”

That’s when Johnny Doyle was painting noble pointers at 5,000 a collar and his social life was much commented upon thereabouts.

My cousin Sally knew him better than I did. “Every time I heard his name,” she sighed, “it was somehow vaguely connected with some minor scandal.”

Doyle wore indifferent khaki pants, fine bloomy linen shirts open at the neck, boat shoes with no socks. The man was a chick magnet. They said he had agoraphobia, the fear of crowds, because he did not show up for parties. Nonsense, of course. If you are even half famous in Charleston, if you went to even half the parties, you would never get another living thing done.

Lordy mercy…nine hundred major works in 40 years. The man poured so much of his heart out on canvas, but there was more canvas than heart, which finally played out. In his final words he praised Charleston as a city of “golden light and long lavender shadows.”

John Carroll Doyle has stepped from the golden light of the city he loved into his own lavender shadow.

Zane Grey fished up to 300 days of the year. But, with all that time on the water, there was nothing more exciting or more compelling than the really BIG fish—the giants of the sea. Blue fin tuna are (even today) still sometimes pursued with harpoons! There’s the story of a swordfish that was hooked at 10:30 in the morning and played until 11:30 that night—only to…! Tales of Swordfish and Tuna will dazzle and thrill any fishing heart. Zane Grey was born in Zanesville, Ohio, in 1872. He was one of America’s most prolific and beloved authors, writing almost ninety books. He died in 1939 in Altadena, California.