Something New Every Day: The Artwork of Greg Beecham

March 5, 2021

SCA Articles

SCA Articles

Greg Beecham’s reverence for God, country and wild places.

Some people are the life of a party. You know the kind I’m talking about. Our tribe of outdoorspeople is filled with big oversized personalities and raconteurs — rambunctious magnetic figures whose mere approach often sounds like advancing rumbles of tympanic thunder.

Greg Beecham, too, has a presence that precedes him. He creates aesthetic auras that fill rooms. They cause us, upon seeing them, to stand stunned in silence, captivated without him having to utter a single word.

Who would guess that Beecham is an introvert? He is an understated picture of humility, in fact — an extension of both his faith and the reverence he has for nature. He lives in an outpost, Dubois, Wyoming, near public lands abounding with the greatest concentration of charismatic megafauna — predators and prey — in the Lower 48.

In contrast to a lot of contemporary wildlife art that merely replicates photographs, Beecham’s scenes float forth with an ambiance of smoky ether. Painted in alla prima — the technique of thick wet brushstrokes piled on top of one another like surface impressions made into sculptor’s clay — his surfaces seize the eye.

But it’s another classic skill he has perfected — sfumato — that sets him further apart. It’s the same method used by Leonardo da Vinci in his Renaissance masterpieces Mona Lisa and Virgin of the Rocks.

Beecham’s works, which hang today in museums and private collections, aren’t just “old worldly” but timeless in that the glory of his subjects cannot be pegged to a particular era. They are, like the rarefied ground our most elusive wild creatures haunt, windows into a mysterious untamed world greater than ourselves.

Talk to Terry Hamby about where he thinks Beecham stacks up. He puts him in the same vaunted category as the late Bob Kuhn and Carl Rungius.

On the day I spoke with Hamby, the businessman, hunter and conservationist who has a whitetail preserve in Kentucky known for its monster bucks, Beecham was on his mind. He was thinking about a mountain lion piece by the artist among nearly 20 originals he and his wife own. The painting, a dramatic nocturne, features a growling cougar laying on a rock in dark moonlight. In the shadows one can see its lithe outline and rippling muscles. As one moves around the room, the feline’s gaze seems to follow you around no matter where you roam.

“I look at the painting every morning while I’m having coffee and notice something different,” Hamby said. “That’s the way all of his works are — impactful. And that’s what great artwork is supposed to do. His scenes have these wonderful little elements that hold discoveries. At the same time, with this piece, he places you right in the moment with the cat.”

What excites Hamby and other Beecham collectors today is that, after decades of making a name for himself with North American big game and avian subjects, winning awards and accolades, he is tackling more African species, such as the lion piece, Savannah Royalty and a recent celebration of Cape buffalo titled A Handsome Fellow.

Historically, only a handful of painters and sculptors have successfully crossed the divide from one continent to another and created convincing portrayals that read true visually to those who know the animals. Beecham has joined the rarefied club.

Multi-generationally, three traditions run deep through Beecham’s lineage — art, hunting and service to country. His father, Tom, (1926-2000) was a Coloradan who became a well-known East Coast illustrator. His adventure paintings appeared on the cover of popular outdoor magazines such as Outdoor Life, in advertisements and on book covers.

Growing up in the Hudson River Valley, Greg was exposed to the rigid tradition that defined top-flight illustrators dating back to the form’s golden age in the 19th century which produced some of America’s greatest wildlife and Western painters.

The competition between them was collegial yet fierce. Toiling under tight deadlines and paid to deliver evocative scenes that would engage the attention of large audiences, they constantly drew human figures and animal subjects from life. “Dad would have my mom and the kids pose in various kinds of positions to mimic the scene he was trying to create,” Beecham said. One might involve a hunter being surprised by a bear or a group of alien invaders. The high standard left an impression on Beecham who, mentored by his dad, absorbed more learning than any elite art school education.

“When I was in about sixth grade, he sat me down and taught me how to draw. I could copy photographs, but I didn’t know anything about art,” Beecham says. “When we went out hunting, half of the time was just spent being together and looking. As we waited for a whitetail buck to move closer, he would describe the reflected light beneath its belly and the rays of the sky on its back and the way it moved. When it came time to decide what I wanted to do, it was to be an artist like him and I couldn’t think about anything other than wildlife, though today I wouldn’t mind painting a person’s portrait.”

Citing the godfather of the Golden Age, Howard Pyle (1853-1911) who served as a patriarchal teacher to many talented sporting artists, Greg says, “You look at the grand paintings Pyle did of people and every single one of the characters in the scene had personality, no matter how large or small. His paintings were not just pictorials. He gave everything that appeared in the painting a sense of life, purpose and character.”

Beecham is praised for bringing the same attitude to his work. His is a family that takes patriotism seriously. His father joined the Navy and served in the South Pacific Theater at the end of World War II.

Three days after he graduated from high school in the spring of 1972, Beecham himself went to Navy bootcamp and then on a guided missile destroyer. When his service to country ended, he and his wife of 43 years, Lu, were married, settling in Seattle where they started a family. He worked as a commercial artist and she coordinated the work of engineers for aerospace company Boeing.

Longing for a quieter life, the couple moved to Wyoming a quarter century ago with their two kids and selected Dubois because it had solid schools and was located between the Wind River and Absaroka mountains in close proximity to national forests as well as Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks.

Quickly, Beecham became one of the rising stars of the wildlife art genre, a sought-out teacher at painting workshops and he gained international notice as he shifted away from tight representations of his subjects.

A turning point happened in 2013 after he suffered a heart attack, his second. As he was in the throes of soul-searching convalescence, he pondered the careers of other established Western painters, some of whom had become quite financially successful by producing differing variations of works with similar themes. He admired their talent, but he wanted something else.

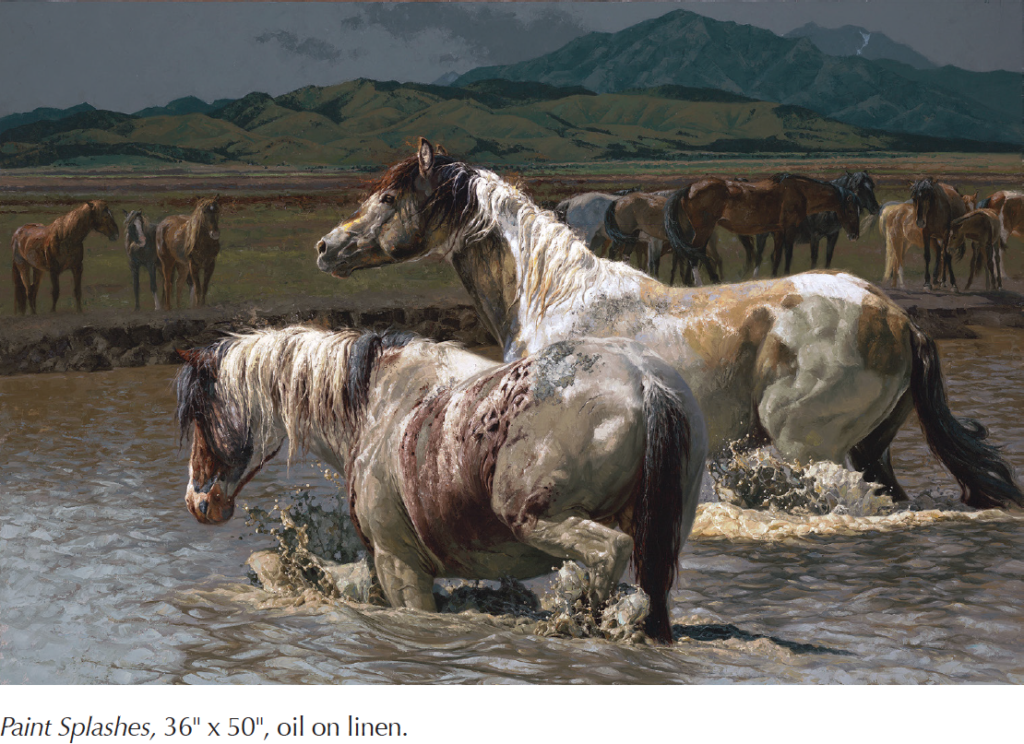

He had a deep conversation with himself, aided by prayer. The answer, he discovered, was already in front of him, for around the same time, he remembers receiving a compliment from artist Thomas Blackshear at the Autry Masters of the American West show in Los Angeles. It came as a response to Beecham’s portrayal of a horse walking through water that Beecham had produced purely for himself, listening to an inner voice.

“Your painting has weight,” Blackshear said.

“I realized, ‘That’s it!’ It’s what I’m trying to do. More or less, sculpt with paint,” Beecham said. “Rather than put in some fine detail with a small sable brush, I really like to create a heftier sense of spontaneity and freshness and being willing to not only apply paint but rework it, and not treat everything I do as being too precious, that it can’t be scrapped or redone better.”

Hamby praises Beecham for exuding courage in midlife when many take the easy road often leading to unremarkable results. “It’s incredibly difficult to make a living as a painter and not give in to market pressures. Greg held out longer than anyone and he wouldn’t compromise his God-given talent to sell a piece of art,” Hamby says. “He’s not painting to create what people want to buy. He’s pursuing his own voice of what he’s inspired to make and it’s why he stands out.”

If there’s a simple statement that articulates what he’s after, it’s being “united in the context of simplicity and beauty,” Beecham says, adding that he admires the work of George Carlson, who spent decades working as a renowned figurative sculptor then shifting to painting. Carlson is the only artist to win the coveted Prix de West Purchase Award in both mediums.

“One of my primary approaches to composition came from studying George Carlson’s sculptures. It is the idea of focal point emanating from a mass, yet remaining part of the mass. He is the only sculptor I’ve ever seen who has been successful in depicting golden eagles in flight in their mating ritual. All others do what my dad used to call, ‘cannonballing,’ everything exploding; wings, feet, tails, heads, all equal size, going every which way, all equally important — therefore nothing being important and nothing holding interest,” Beecham says. “George brilliantly solved that problem by placing a mass of rock wall from which the figures emerge and hold together. Then I got to looking at his whole body of work, and he used that approach many times, with his usual genius.”

In Beecham’s works, especially those of the past decade, there has been a noticeable shift toward abstraction with paint taking on more weight and volume. Abstract shapes within other abstract shapes and then even more after that, all adding up to a recognizable image when viewed from a distance, but up close it might appear as fragmented flurries of color brilliantly arranged.

“One of my favorite observations comes from [Montana landscape painter] Clyde Aspevig who says, ‘painting is easy; there are only 1,000 things to remember at the same time.’”

In Beecham’s execution, a viewer can see that colors introduced in the lower right of a painting are repeated or continued in the upper left. Through his sophisticated melding and using soft edges at points of transition, he is after achieving a seamless harmony of color, texture and shape.

Particularly following his health scares, Beecham is effusive in his gratitude to a higher power. “Obviously, when I look at nature, I see God’s work and communicating it is an act of worship,” he says, referencing writer Dorothy Sayers, a contemporary of Christian writer C.S. Lewis. “She wrote that the first thing we know about God is he liked to make stuff,” Beecham says. “God created man in his image, male and female. I too am created in his image and have this built-in need to make stuff. I consider that my work as a painter, being an image bearer, to be an act of worship.”

The Beechams have had moose, elk, mule deer, pronghorn, bears and wolves pass through the mix of sagebrush and forest near their home. During a drive to Jackson Hole to pay a visit to the National Museum of Wildlife Art, Beecham came upon a grizzly digging bitterroot on Togwotee Pass. He watched the bear, gathering reference material.

Outside Dubois, too, is the famous Whiskey Mountain bighorn sheep herd that inhabits the northern reaches of the Wind River Range. Basking in the Winter Sun, a tribute to two brother rams, is yet another example of him painting what resides in his heart.

In recent years at high-profile shows, Beecham has won viewers’ and artists’ choice awards for his action scenes. Most gratifying, he says, is receiving validation from his peers. One piece, Feathers and Dust, was recognized with the Wildlife Award at Prix de West and later a collector donated it to the Biscoe Museum in San Antonio.

The piece is a dramatic presentation of a golden eagle dive-bombing a jackrabbit in the Red Desert of Wyoming. He gathered the material by joining falconers. Critics say the work puts Beecham in the same league as Bruno Liljefors, Sir Edward Landseer and the acclaimed contemporary watercolorist, Thomas Quinn.

There’s nothing Beecham can’t paint, and his portfolio extends to horses and bird dogs. Hamby commissioned him to create an epic scene at his private whitetail hunting ground. The artist flew to Kentucky and spent two days with Hamby and his grandson spying for deer at dawn and dusk so that Beecham could create the mood he wanted.

The resulting work is a marvel not only of subjects but of design and composition. A group of does and bucks are pictured crossing a stream flowing through Hamby’s farm. “He offers a focal point where your eyes enter the scene but then, over time, with each visit your eyes wander and you discover things, little flourishes of technique or subtleties that he has created just waiting for you,” Hamby says. “I enjoy the work with a sense of newness every day.”

Beecham has been to Africa with his son and though he’s hunted most of his life, his time spent with wildlife these days is observing animals for paintings. Not long ago, he and Lu went on safari with an artist who worked on the wildlife animation side of the Disney Company. They went to Masai Mara National Reserve in Kenya that abuts Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park. Beecham has had plenty of memorable encounters with wildlife but that trip he describes as “life-changing” and shares the story behind Savannah Royalty.

In the company of Masai guides, they spent an entire afternoon watching a pair of lions engaging in mating only 20 yards away from their Range Rover. Lu pointed to another safari rig filled with tourists wielding cameras and wryly remarked, “They are photographing wildlife porn and we are photographing art.”

Aside from the mirth of the statement, with Beecham it’s true. Every aspect of natural history informs his understanding of a subject and he doesn’t paint anything he hasn’t seen.

“We think of the Greater Yellowstone region being full of wildlife. It doesn’t compare to what can still be found in places on the African savannah,” he says, describing a visit to a place known as “the marsh.” Appearing as a green patch from the air, the convergence of jungle, plain and water yielded every major African species, plus myriad antelope, birds, hyenas and bands of baboons. “It had to be what Eden looked like and every day was similar,” he adds.

Today, as a result, he has a long list of scenes he intends to paint, along with the dozen or so works that he sends to shows at the Prix de West at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Center in Oklahoma City, Briscoe and the Western Visions autumn show at the National Museum of Wildlife Art.

Now there’s a third generation Beecham carrying on the artistic legacy. His daughter is pursuing a career in interior design and applying some of the same skillsets Beecham learned from his father. He mentions his son who serves in the Army National Guard, based in Wyoming and who narrowly escaped serious injury when an IED exploded beneath their Hummer in Iraq.

After a friend’s soldier son died in a different incident in 2004, Beecham asked his son, now 34, if he understood the consequences. “I want to serve my country and am willing to die for it,” he told his dad, whose voice cracks recounting their conversation. Beecham notes, “He is my hero.”

With so much uncertainty in the world, it’s ironic perhaps that there has never been greater clarity for Beecham about the painter he wants to be. For him, it comes down to having faith and believing in the power of things greater than self. “Unity within the context of simplicity and beauty.” That’s his mantra and it doesn’t get any better than that.