Bob Kuhn: Animal Aficionado & Artist Extraordinaire

March 11, 2021

SCA Articles

SCA Articles

Bob Kuhn captured the essence of animal majesty, behavior and drama better than anyone with his distinctive style of painting.

It was Christmas 1969 when I first saw the 1970 Remington Arms calendar featuring “Great Game of the World.” My father and I shared a love of the outdoors and we spent many days hunting and fishing together. At the time, my family lived in Kenya, East Africa, where my father and I took advantage of the opportunity to hunt African big game on our own.

We hung that Remington calendar on a wall near the dining room where it could be seen and admired and, with each month, my imagination was stoked by a new Bob Kuhn illustration showcasing one of the world’s “great” game animals. Kuhn’s distinctive painting style detailed not only the animal’s individual features and traits, but also portrayed the drama of hunting scenes where the animal was often the aggressor, if not an artful dodger.

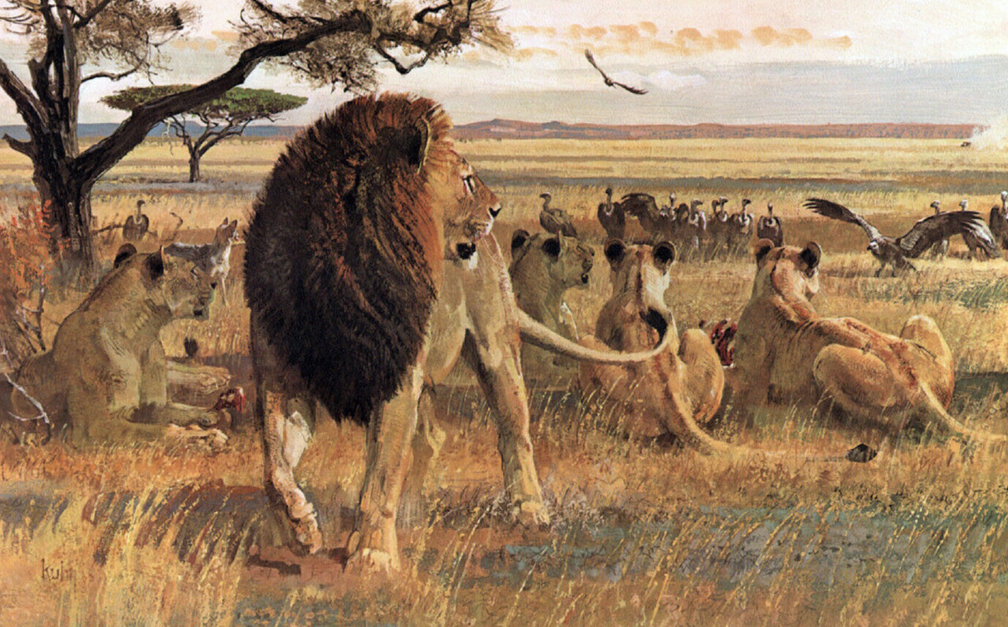

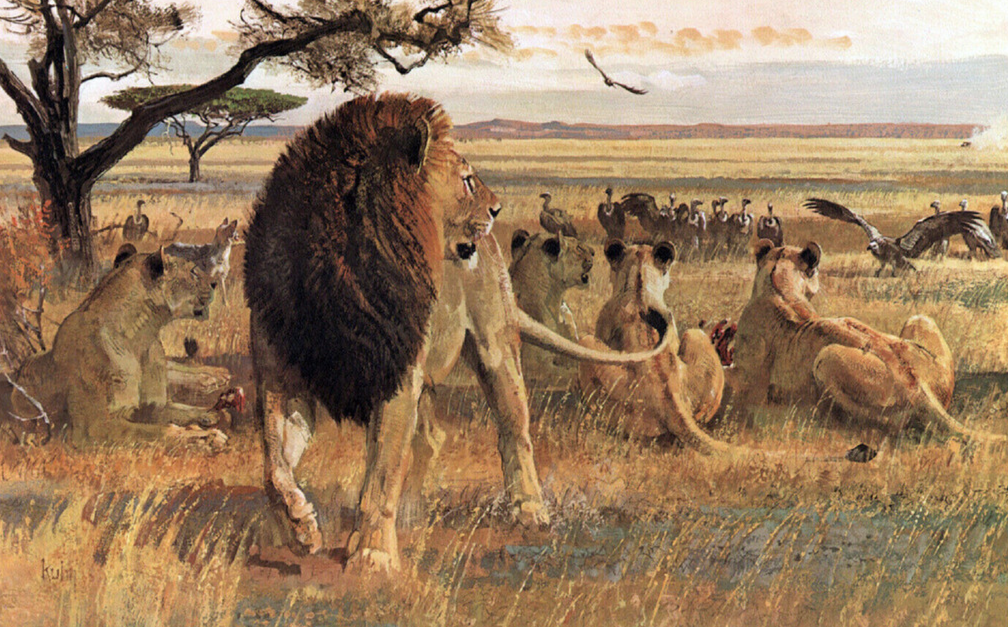

For the month featuring Kuhn’s African lion, called “Interrupted Dinner,” a pride of lions on a zebra kill watch billowing dust across a vast plain as a large-maned male lion stands and also looks. The dust trail is from that of an approaching vehicle. You can just imagine this big male lion is about to head for cover without waiting to find out what the intentions of the vehicle’s occupants might be.

Other months featured a pair of Alaskan bull moose loping “Across the Tundra;” a leopard on a bait is “Out on a Limb;” a “Chancy Encounter” features a grizzly bear confronting a hunter; an African elephant stands over a downed bull and looks as if he’s “About to Charge;” a Marco Polo “Sheep of Shangri La;” a pair of bull sable antelope spar in “Courting Challenge;” and a Cape buffalo is “Turning the Tables” as a tracker dodges a buff’s hooked horns.

“Turning the Tables” is still my favorite, clearly demonstrating the drama and danger of hunting Cape buffalo. The painting depicts a hunter and his gunbearer loading and aiming their rifles to stop the buff attack with bullets. The painting conveys an intensity that clearly warns “watch out!” and illustrates so well how quickly things can go wrong. Studying the scene gave me a real case of the chills. I would come to personally experience Kuhn’s depiction of a dangerous situation more than a few times during the course of my 30 years as a professional hunter in Botswana and Tanzania.

“Turning the Tables” captures the essence of a dangerous game encounter, where often it’s only a knife’s edge worth of difference that separates thrill from danger. Kuhn leaves the outcome of the scenario to your imagination. Today a framed print of “Turning the Tables” hangs in my office — still impressing me with the magic of Bob Kuhn’s brush strokes.

Bob Kuhn was fascinated with Africa’s big game, especially the Cape buffalo. His paintings of “black death” radiate his admiration and respect for the big bovines. He once wrote, “Buffalo have a hard time not looking menacing. They usually run from the intruder, but not always, and that’s what you have to bear in mind during any confrontation. For anyone on foot, the possibility of getting hurt is real.”

Robert Frederick Kuhn was born in 1920 and grew up in Buffalo, New York. As a youngster, he began to observe and draw animals at the nearby Buffalo Zoo.

He was an artist in love with animals and his fascination with them inspired his habit of close observation and drawing for the rest of his life.

In 1937, Kuhn attended the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY, where he studied design, anatomy and life-drawing. He served in the Merchant Marines during World War II and, while on board ship, began illustrating for sporting publications. By the time he was 25, he had sold several covers to Outdoor Life and Sports Afield magazines. He was also a regular contributor to Field & Stream magazine through the 1940s, 50s and 60s.

Over the next 30 years, Kuhn became one of the most successful wildlife illustrators in America, his work appearing in dozens of popular publications. Kuhn did extensive research in creating his works of art. He would spend days at the American Museum of Natural History in New York studying the animal mounts. Despite the success of his early years, Kuhn always claimed he was not a very good illustrator. In fact, he believed his creativity was constrained by the demands of business “to get the facts straight.” Worse, deadlines often required that he submit a piece regardless of his own dissatisfaction with it.

In the early 1960s, Kuhn was invited to work on a project with Jack Mitchell, Remington Arms’ director of advertising. For many reasons, Kuhn was considered to be one of the best-known outdoor illustrators, highly sought after by not only the magazine world, but also among New York City-based advertising agencies. His bold, assured style had made him one of America’s finest animal painters and clearly he was the natural, logical choice for this assignment.

This project would entail yearly calendars to be illustrated with original artwork that would be distributed to Remington dealers and personalized with the dealer’s name. The Remington Calendar was launched in 1966, celebrating 150 years of Remington history and its success was attributed largely to the talents of Bob Kuhn, whose illustrations had both mass appeal and frame-worthiness. Throughout his artwork, you can sense Kuhn’s love of nature, excitement of the hunt and passion for the outdoor life. If anything, the 1966 calendar proved even more popular than expected and limited-edition prints of Kuhn’s calendar art were issued. Over a five-year period, Kuhn produced more than 70 original works for the calendars.

Kuhn’s artwork eventually evolved into the fine art of painting animals in their natural habitat in a style that was unique, sensitive and truthful. In 1970, Kuhn turned exclusively to easel painting, often painting simple backgrounds with horizontal bands of color and light to capture particular movements and personalities of wild animals. He worked primarily in acrylic and was well known for his ability to paint the particular movements and personalities of wild animals.

Kuhn was not only the pre-eminent animal painter of his time, but he was also a skilled outdoorsman, handling a fly rod, shotgun and rifle as deftly as he handled a paintbrush. Long recognized for his skill at capturing the essence of an animal’s movements and for his detailed compositions, Kuhn traveled from Alaska to Africa to study his subjects in their native surroundings. He and Libby, his wife of 66 years, traveled around the world to obtain inspiration, with many of their wildlife expeditions lasting several weeks.

In 1975, Bob Kuhn traveled to Botswana with Harry Tennyson and a group from San Antonio-based Game Conservation International (Game Coin). Bob’s main objective was to shoot big game with film and camera to provide reality references for his artwork.

Peter Hepburn, a fellow professional hunter with Kasane-based outfitter, Hunter’s Africa and a friend of mine, guided Bob in his efforts to capture on film Botswana’s big game in action. At the time, Hunter’s Africa roster of professional hunters included several respected Kenya hunters including John Lawrence, Fred Bartlett, John Dugmore and John Northcott, as well as Botswana’s Bert Milne and Peter’s father, Pat Hepburn.

Peter and Bob camped in the forest on the banks of the Linyanti River, a prime big game hunting area in Northern Botswana. The forest was thick back then, not yet destroyed by the overpopulation of elephants that has occurred during the past 20 years. Hunting tracks twisted and turned through the forest, often blocked by broken trees and strewn with brush pushed there by elephants. Frequent stops were necessary to clear the road and confronting angry cows was of constant concern. On several occasions, they had to make rapid, nerve-racking escapes from charging cow elephants without knowing whether the road ahead was clear.

“Bob wanted as many photos as possible of animals on the move,” Peter remembers. “And I’m sure he got some great action shots of elephants with those exciting encounters in the thick riverine forest, although possibly not all in focus. We also had to contend with the ‘dreaded tsetse fly.’ That was years before the Botswana government carried out an extended eradication program.”

In spite of charging elephants and biting tsetses, Bob was able to get the action shots he wanted of loping giraffe, zebra and other running game. Peter remembers feeling quite anxious as Bob would lean half-way out the door of the bouncing Land Rover while the vehicle careened down rough bush roads as they tried to keep up with galloping game.

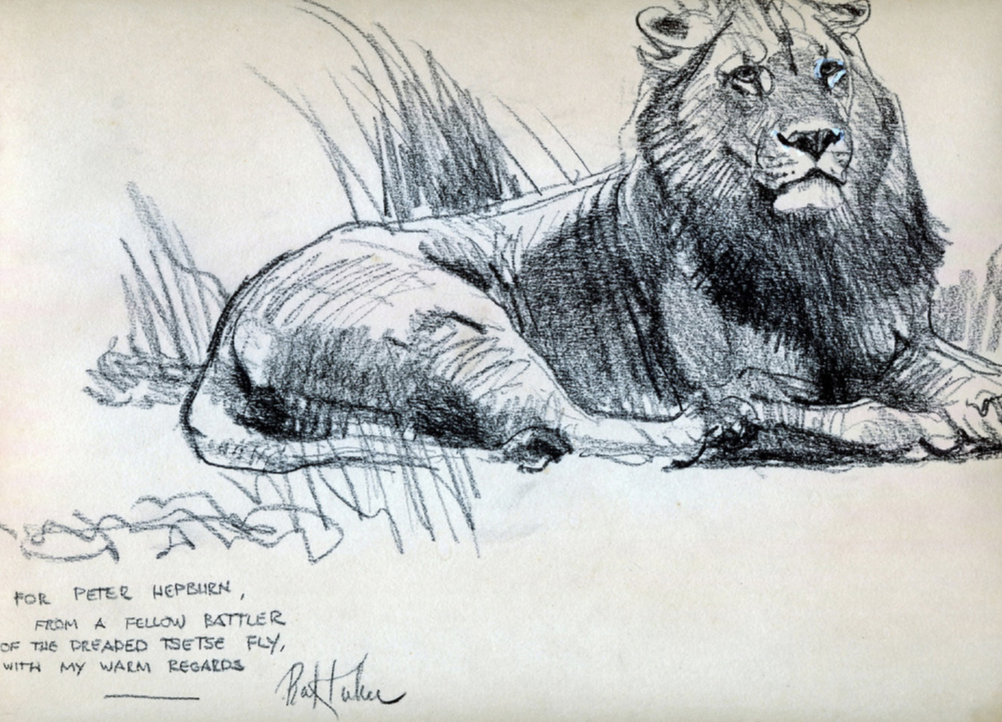

“Fortunately, the door remained closed and Bob got some excellent close-up action shots,” Peter recalls. “He was a very easy man to please, and very appreciative of my efforts and those of Hunter’s Africa in helping him get material for his art. It was a wonderful privilege for me to introduce Bob to Botswana’s spectacular big game. As a thank you, he sketched a lion for me with a personalized message, which I treasure.”

I was also privileged and honored to have met Bob Kuhn in the mid-1980s when Jim Codding, a mutual friend who also collected Kuhn’s work, introduced me to him. I was especially pleased to be able to tell Mr. Kuhn how much I admired his work and how big an impact his 1970 Remington Calendar had on me and my impressions of Africa.

Sadly, on October 1, 2007, legendary illustrator and gallery artist Bob Kuhn died in his home in Tucson, Arizona, at the age of 87, after a long battle with heart problems. Someone described it best when they said, “The passing of Bob Kuhn leaves a huge hole in the world of art that I doubt will ever be filled, and an even bigger hole in the hearts of those of us who were lucky enough to know him.”