Ezra Tucker

March 19, 2021

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

A commercial illustrator who created work enjoyed by millions is now making his mark in wildlife art.

In Ezra Tucker’s painting, Freshwater Paradise, a tom cougar lounges in the understory of a cypress swamp as a flock of egrets passes ethereally through rays of sunlight. Here, the artist is returning the biggest of America’s wild cats—our version of African lions—back into primordial lairs they are haunting again after nearly a century of extirpation.

And for Tucker it is a homecoming worth celebrating.

Were it not for his signature laid down in acrylic paint, however, one could easily assume that this sweet meditation might instead be the handiwork of some long-departed master—Bob Kuhn perhaps, or maybe the legendary Charles Livingston Bull, best known for illustrating Jack London’s The Call of the Wild.

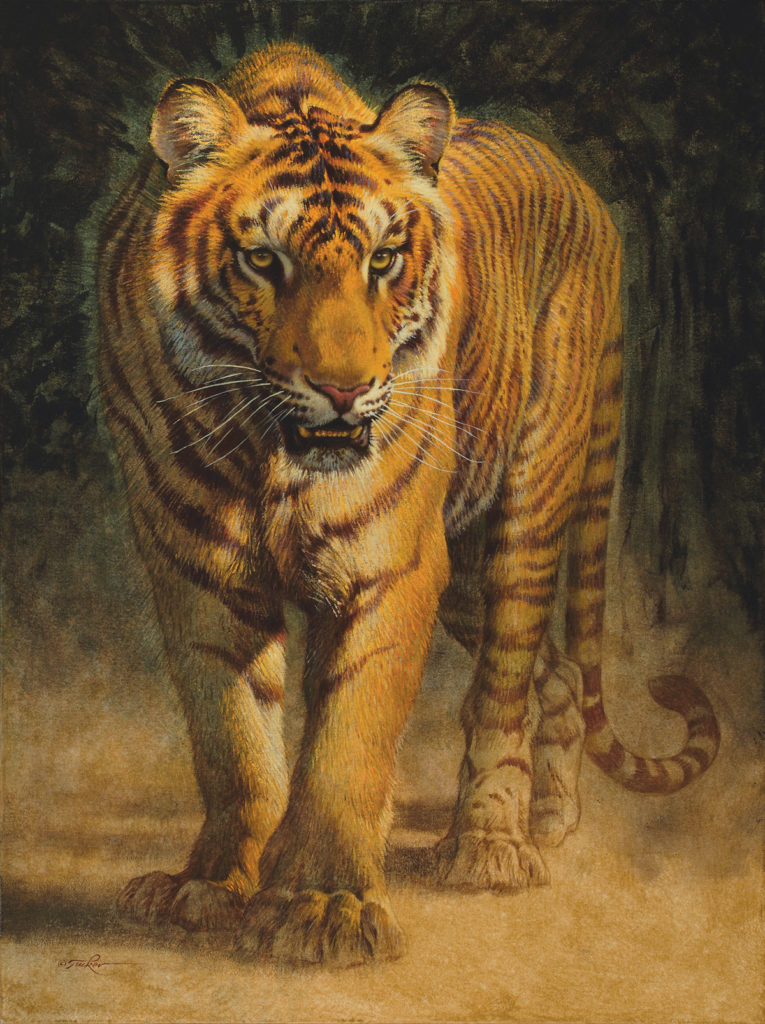

Indeed, the caliber of the composition, the soothing harmony of color and more strikingly, the tranquil, mysterious mood radiating off the surface, warrant the comparisons. We see it, too, in his portrayals of a bear and wolves sparring over a carcass, studies of foxes, wild mountain sheep, Cape buffalo, and charging rhinos.

Which, of course, summons the question: Why haven’t we heard more about Tucker and his remarkable portfolio? The simple answer isn’t that Tucker, at age 62, could be described as a late bloomer—he isn’t; nor is it a matter of not seeing his work. Ironically, millions of us already have, which in a way gives his art an air of familiarity.

For this uncommon, media-shy easel painter from Monument, Colorado, who has a view of Pikes Peak rising in the distance from his studio—the secret of his work, heretofore savored only by a relatively small number of collectors lucky enough to own a work, is rapidly spilling out.

“His style is so unique,” says Jimmy Huggins, president and CEO of the Southeastern Wildlife Exposition in Charleston, where in 2017 Tucker was the featured artist.

“When he first came to the show, you could recognize the superb quality of his work right away. He brings a look that is Old World and mature, but it also has a contemporary feel that gets your attention,” Huggins said, noting that Tucker is an artist whose virtuosity speaks to both seasoned and younger collectors.

Ralph Oberg, another vaunted wildlife artist who lives on the western slope of the Colorado Rockies, contacted me earlier this year recommending that I look into Tucker’s exciting series of new works. He described Tucker as one of the most talented yet underpublicized animal painters in America. Naturally, I was intrigued.

Oberg is not one to dole out praise casually, for he hangs out with a distinguished clique of colleagues counted among the best living Western artists. They have high standards for excellence.

“I like Ezra Tucker and his work a lot,” Oberg said. “It is so unique and beautifully handled that he deserves attention. He is on the cusp of becoming a household name.”

In other words, so rare is the opportunity for a collector to own a piece by an artist who is on the verge of achieving true stardom.

On so many different levels, Tucker is an enigma in the world of contemporary wildlife art—in one sense a disciple of the grand, Old World tradition of painting and America’s Golden Age of Illustration—and yet his work possesses an engaging, modern approach to composition so aesthetically alluring the eye cannot look away.

When Tucker paints, it is with a deeply personal conviction that animals are life forces. He does not create merely to commemorate or render subjects. Instead, his scenes activate a wild spirit in the spaces we inhabit.

Indeed, it’s telling when I asked him to provide a short list of talents with whom he finds kindredness. Many were former illustrators who later found greatness as studio painters. He mentions Philip R. Goodwin, Arthur Wardle, Wilhelm Kuhnert, Carl Rungius, French animal sculptor Antoine-Louis Barye, Fenwick Lansdowne, John James Audubon, Rien Poortvliet and one of the sensations of 21st century nature art, Walton Ford. Yes, it’s one thing to mention influences, including Kuhn and Bull; it’s quite another to audaciously execute on their level.

Born in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1955, Tucker says the rural countryside and being able to explore the humid forests and bayous of the Mississippi left an imprint on him. Early on his prodigious talent for drawing was recognized, and it earned him praise and an entrance to the Memphis College of Art, where he earned a degree in advertising design. One of his earliest desires, he said, was working as an illustrator making the kind of paintings worthy enough to appear in magazines.

“When I entered college in 1973 saying that I wanted to be a wildlife artist, I was told that this was impractical to pursue. There were no classes for that. The closest discipline to do wildlife art was in illustration. So I signed up for illustration and tortured my instructors by incorporating animal images into every class project that I was assigned,” he says. “I drew the human figure well and wanted more of a challenge and took every opportunity to study in the local zoological garden, school and public libraries reference books on European animal artists and impressionist painters.”

A short while after graduation, he landed a job in Kansas City working in the stable of Hallmark greeting card artists. Among them was the renowned contemporary painter Mark English and Tucker’s future wife, Nancy Krause.

“Mark would critique my work, and he and I would have long conversations about the importance of pushing your own limits,” Tucker says. “I met him when I was in my early twenties, and he gave me advice I’ve never forgotten. He always encouraged me to take risks and experiment, to never, ever stop experimenting, because that’s how you become original.”

Tucker and Krause had a mutual desire to confront bigger projects and tougher artistic challenges. Seeking their destiny, the couple moved to Los Angeles. As a freelance illustrator, the quality of Tucker’s work attracted both critical attention and prominent assignments. He designed the visuals for Anheuser-Busch billboard advertisements, featuring the iconic Clydesdale horse team, that appeared before literally millions of motorists traveling along the interstates. He had gigs doing work for Pepsi, Coca-Cola, Bank of America, the MGM Grand and Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, Levi-Strauss, Seagram’s and others. But among his most memorable work, in hindsight, was painting posters, just as others like Howard Terpning had done for Hollywood studios such as Disney, Warner Brothers, Universal Studios, 20th Century Fox, Paramount, Lucas Films and Steven Spielberg. He hobnobbed with actors and directors, some of whom collect his work.

Along the way, he never lost his connection to nature and painting wildlife, landing images in Outdoor Life and Field & Stream, in addition to designing visuals for The Brookfield Zoo and Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, the National Park Service and others. Even after moving out of LA to Solvang, where he and Krause started raising their family, and where Tucker made paintings of Arabian horses for prominent local breeders, he felt restless in crowded southern California. The family moved to the western interior to live closer to wild country with their children, Noel, Maclin and Nelson.

Tucker finds photo-realistic portrayals of animals to be too static and not nearly as imaginative as the impressionistic visions in his head.

“My wife told me, ‘If you are really going to do this, really make it as a wildlife painter, you’re going to have to take risks by being true to yourself.’” That advice paid huge dividends.

As overtly enchanting as his work is, Tucker himself is soft-spoken if not quietly cerebral.

“Painting wildlife in a realistic, stylized manner allows me to define the beauty that I see in their movements, be they subtle or overt,” he says. “I choose to highlight the variety of color I see in the fur and textures of the surfaces that envelop their being.”

With Nomads of the Plains, for instance, which depicts a pair of pronghorns, he tips his hat to the romantic painters of the 19th century.

“I approached this painting as a Victorian period naturalist might approach creating an image descriptive of a species that is newly discovered,” he says. “My challenge was to capture the color, beauty, and present it in a way that is visually stimulating.”

In the work Desperate Challenge Tucker shows his admiration for the predicament scenes that defined outdoor magazines during the Golden Age of Illustration at the dawn of the 20th century.

“This painting is reflective of my career as an illustrator of short stories in Boy’s Life and Field & Stream. Here, I imaged the dramatic encounter of a pack of wolves and a grizzly challenging the others for the right to feed on a moose. But who made the kill, and who should make claim to it? This is a question best left for the viewer to decide.”

What the viewer may not appreciate at first is the sophisticated layers of underpainting that add texture to Tucker’s surfaces. Buried even deeper beneath the brushstrokes are pencil sketches based upon years of observation and, when possible, drawing from life.

Wielding a discipline he perfected during his illustration days, when he had to work up compelling compositions under tight deadlines, Tucker is known for his designs.

“He is so masterful. He practically fills a whole sketchbook for each painting to ensure that all of the elements come together,” says Chrystal DeCoster, co-owner of Western Stars Gallery in Lyons, Colorado. “When you stand back, the painting reads realistically, but move closer to arm’s length and you realize how sophisticated his painting is, with abstracted brushstrokes and surface texture that invites you to go knuckle-deep into the essence of the animal.”

While Tucker prefers not to be labeled within the confines of a single “ism,” such as Realism, Impressionism or anything else, stylistically he’ll admit to identifying as a nouveau Victorian, meaning that his compositions are inspired by classical approaches to composition. He knows how to achieve big visual impact.

More than a decade ago, in the years after Tucker gave up a lucrative career in commercial illustration and left California to settle in the Colorado Rockies, he first heeded an impulse to paint something truly monumental. So he conjured a life-sized grizzly standing on its hind legs towering seven feet high. Naming the piece Roosevelt in honor of America’s greatest conservationist president, he delivered it to a gallery in Aspen. Immediately, the artwork became a sensation to passersby and within a matter of days it sold. Word quickly spread, and soon Tucker received commissions to deliver life-sized representations of other species.

Hearing about the painting and the commotion it caused, Maryvonne Leshe then saw more of Tucker’s work at SEWE.

“Why don’t I know of you?” she asked.

Leshe, the managing owner of Trailside Galleries in Jackson Hole and Scottsdale, asked Tucker to paint another bruin—a nine-foot-tall piece that took him three months to complete. It ended up filling a wall inside a collector’s trophy room.

Not long ago Tucker sent Trailside a grand moose painting that left viewers standing beneath it spellbound. This fall, Tucker’s work is being featured in a show at Trailside.

“With Ezra’s work, you feel the genuine love he has for the soul of the animal,” Leshe says. “Revealing it is his primary focal point, and he invites us to share in his feeling of reverence.”

Notably, some of Tucker’s most ardent collectors don’t want mounted heads in their living and dining rooms, yet they purchase Tucker’s art to honor their passion for the outdoors while giving an elegant touch to the spaces where family and friends gather.

Tucker wants to give his subjects the majestic dignity he believes they deserve, viewing his paintings as homages to the planet’s miracle of lifeforms that were millions of years in perfecting.

“The intelligence and uniqueness of each animal’s individual character and personality often provide glimpses into that of human nature or character,” he says. “I believe that we are more connected to one another through habitat and survival than most humans acknowledge. People who are out in the wilderness, following in their tracks, know it better than anybody.”

Editor’s Note: Todd Wilkinson, whose work has appeared in National Geographic, has been writing about art and the environment for three decades. He is the author of several award-winning books, including Grizzlies of Pilgrim Creek, An Intimate Portrait of 399, the Most Famous Grizzly of Greater Yellowstone.