The Art of Mort Künstler

June 25, 2021

SCA Articles

SCA Articles

You’ve just humped up a steep knoll trailing a wounded elk or maybe you have designs on glassing mountain goats. Fatigued, out of breath, a stiff headwind numbing the frontal cortex of your brain, there’s no time to react, other than getting a jolt of adrenaline.

Mere feet away, a grizzly bear mother rises. Agitated and surprised by your advance, she is standing on hind legs eyeballing you, ears pert, scent-whiffing, swatting at the air with her claws and clicking her teeth.Poised to charge in defense of her cubs, she has you at her existential mercy—which also happens to be exactly where Mort Künstler wants you to be, too.

Künstler is legendary for making our spines tingle. From portraying historic military battles to the narratives of detective whodunits, from illustrating fantastical tales of science fiction to depicting seedy cultural noir, in every direction his scenes have unfolded across a panorama of adventure, drama and passing human generations.

For more than 70 years, in fact, the American painter has brought warmth to our searching souls and spurred our hearts to beat faster. With style and magic in delivering two-dimensional illusions, Künstler has transported our imaginations into different states of mind and, when he’s feeling mischievous, he hasn’t hesitated to tickle our funny bones.

“Mort always describes himself in simple terms as that of a storyteller,” says Dr. Michael Schantz, executive director and CEO of the Heckscher Museum of Art in New York, one of several high-profile venues that have showcased Künstler’s work over the years.

Yes, Künstler’s modest description of his own role holds, though Schantz notes that he tells stories the way masters of the Renaissance did.

“Between his classical training and the sophistication of his compositions, his designs have been contemporary but his instincts as a painter are Old World,” he points out.

Younger readers here may not readily know Künstler’s name, perhaps because he commands distinction as one of the last of his kind—descended by tradition from what once was called “the Golden Age of Illustration.” It was an era when fine art fulfilled a grand public purpose, creating common visual reference points for the way American masses identified as a nation. To put Künstler in perspective, his tenure overlapped with the late great Norman Rockwell.

Mort Künstler’s work has been seen by untold millions, appearing on the covers of novels, magazines (including many we savor in the hunting and fishing genre), movie posters and collectible prints based on his most memorable works that today adorn walls of homes and offices across the country. Nearly three dozen books also feature his illustrations.

“When people try to dismiss illustration and realism in art, I tell them that Michelangelo was an illustrator and he did pretty well with painting dramatic scenes that qualified as fine art, didn’t he?” Künstler says. It’s worth noting that in German, the word künstler means artist.

“Mort has had the skills to do anything,” says Schantz. “I’ve seen, for example, thirty dinosaur drawings and little sketches. They’re as good as any you’d find in a natural history museum.

“His forte is conveying movement. I love how he directs the viewer’s eye, be it a painting of World War II, gangsters or a hunter getting startled by a predator. Embedded within him is the ability to use every artistic trick in the book relating to perspective and the drama created between light and dark.”

In this post-modernist era when so much fine art is obscure, experimental and non-representational (i.e. there is no clear subject or theme), Künstler arguably represents a touchstone. As an acronym, MAGA certainly has one connotation, but for this writer, there is another: “Make Art Great Again” and for me, Künstler’s body of work, as a reference point, would be an exemplar.

Indeed, these days it’s difficult to find a living painter who knew—and stood literally alongside—those whom we regard as the legends of sporting art; it is almost unheard of to find a contemporary who still wields a brush with such flair and is so lucid of mind as Künstler .

Born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1927, Künstler became recognized early on as a child prodigy, talented artist and a fine athlete (who would earn a basketball scholarship to UCLA). By the time he graduated from Pratt Institute, illustration, at least as it had been, was dying.

“I spent my entire career, from then until now, never a day without work. I’ve always had an assignment hanging over me, but I never considered it work. I couldn’t believe how fortunate I felt when I started to see my pictures being reproduced and circulated. I’d say to my wife, ‘and they pay me for this, too’.”

Künstler said that family friend, illustrator George Gross, was a mentor but he derived stylistic inspiration from artists such as Winslow Homer (who was an illustrator during the Civil War), Frederic Remington, N.C. Wyeth, Charles Russell and numerous Golden Age talents that followed in their wake. Künstler has one of the most impressive private collections of works by Golden Age illustrators in the world. A major break in his career came when the Hammer Gallery in New York City staged a one-man exhibition in 1977, the first of 15 solo shows that solidified his standing as a giant in American realism. He is considered today the foremost painter of the Civil War and other turning points in history.

For example, he is responsible for several works that have become reference points, whether it was Lee and Grant at the surrender talks at Appomattox Courthouse, the aftermath of Gettysburg, George Washington crossing the Delaware, or even a portrayal of the USS Indianapolis, the Navy vessel that was sunk by the Japanese and involved the greatest single loss of life at sea, which included deadly encounters with sharks.

As an artist, Künstler has been called “an American treasure” by a number of prominent historians.

What makes for a great narrative painting?

“There’s no simple answer,” he says. “I have a little saying that I tell myself, ‘If you’re going to tell the story, tell the story. Use every tool an artist has—perspective, light and dark, color, contrast—everything to tell the story and it seems to have worked. Make the viewer’s eye go where you want it to go.”

Among the illustrators, who in the greater New York City area represented the finest massing of realistic painters in America, Künstler says there was always a friendly competition as artists competed for prestigious assignments. Still, there was plenty of sharing, he notes.

Unlike many of his colleagues who left the East Coast as illustration went on the wane and decamped in places like Tucson, Taos, Santa Fe and Scottsdale, Künstler remained on Long Island. While some took up Western subjects and gained even more fame and recognition in “Western art,” Künstler remained in demand as an illustrator. Prestigiously, he was recruited to be an illustrator for National Geographic magazine in 1965.

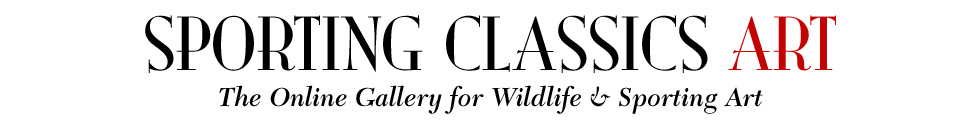

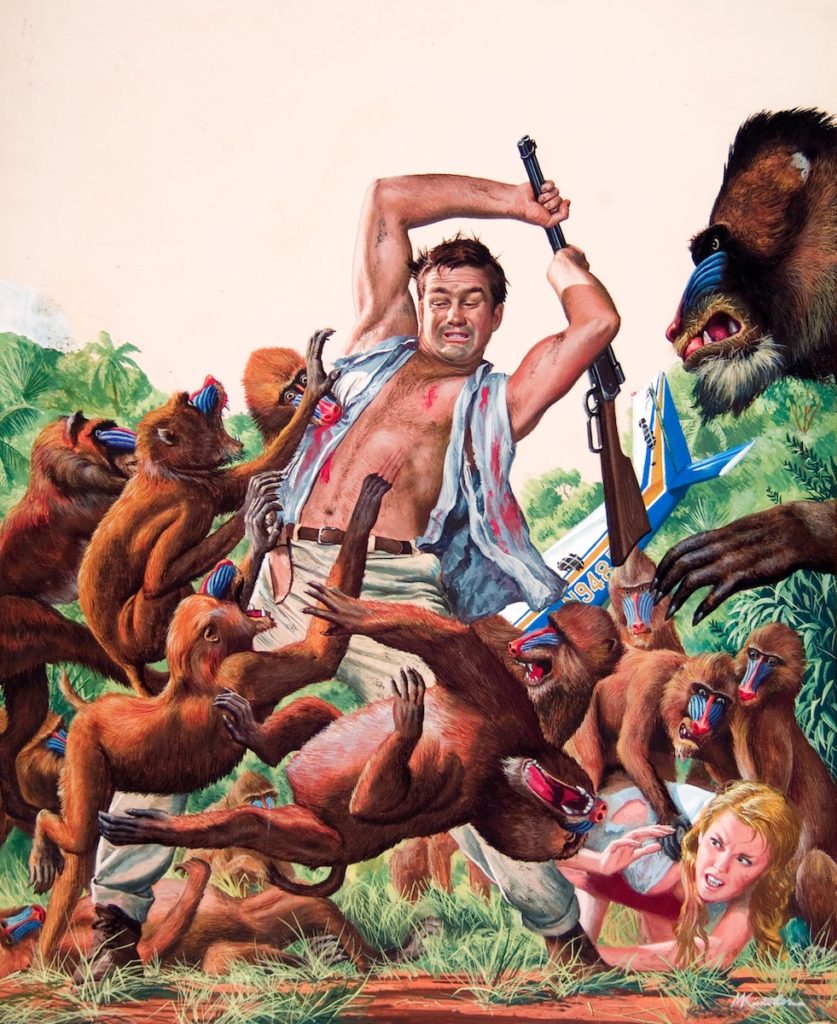

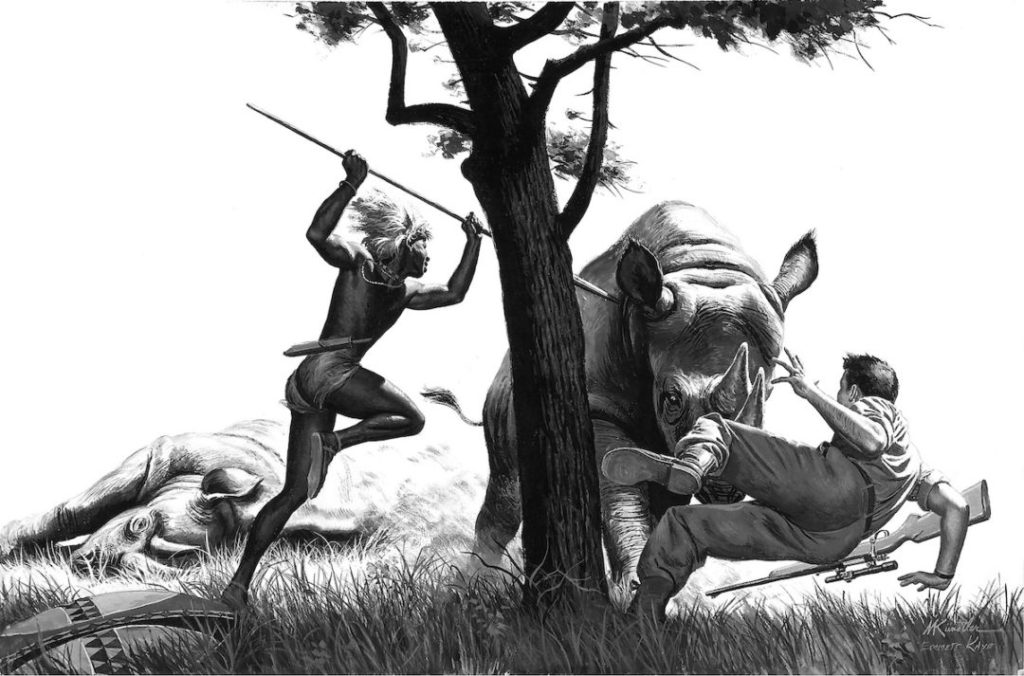

When the exhibition opened at the Heckscher in August 2019, more than 70 pieces were featured. Many of those works have never been publicly displayed. Given both Künstler’s and Schantz’s concern for the fate of the natural world, particularly their concern about the impacts of poaching, the show is rich with the painter’s “animalier” between humans and wildlife. Explains Schantz: “We highlight a lot of different genres Mort has explored, but the animal versus man category is certain to command attention, especially those scenes in which the animal is getting the best of the characters presented on two legs and sometimes getting a leg up on their would-be tormenters.”

In one picture, Schantz notes, Künstler portrays an African elephant just as it is about to squash a human protagonist with its front leg. Such portrayals fit the classic definition of a predicament scene, the kind that used to adorn the covers of adventure magazines found on newsstands and in barbershops.

Like potboiler plots in pulp fiction novels, predicament scene paintings delivered viewers into circumstances in which the outcome was uncertain; the artist asking us to ponder what the conclusion would be.

Although predicament scenes were not Künstler’s main focus, his longevity and prolific output has earned him worthy comparisons to other legendary sporting painters who were better known, such as the late Bob Kuhn who had profound admiration for Künstler. (Künstler was a friend of Kuhn’s and both were alumni of Pratt.)

“I always had fun painting animals and the interactions humans had with them,” Künstler says. “I like giving nature the upper hand. There’s a wonderful wild world out there. I’ve always thought that if people can’t physically travel to see it, I can bring it to them. Everyone could use having a little more adventure in their lives.”