The Evolution of a Masterpiece

July 28, 2020

SCA Articles,Uncategorized

SCA Articles,Uncategorized

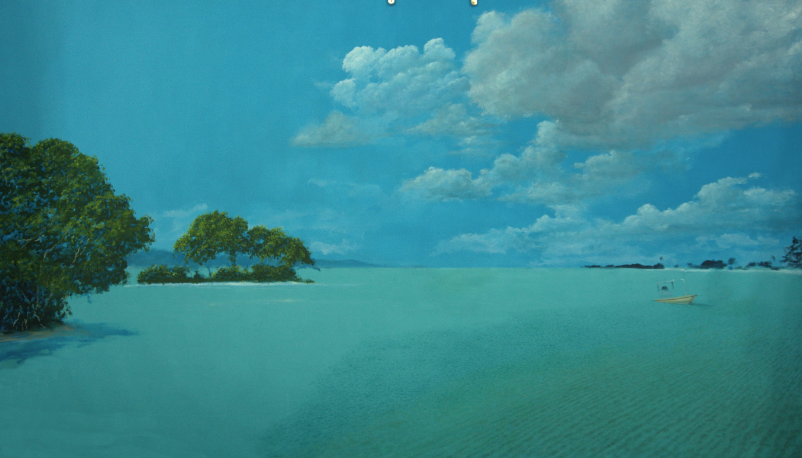

The seven stages of creation for sporting artist Keith Cardnell’s alluring painting Finding Silver in Thin Water

When we view a work of art, whether at a gallery, online or at home, we see a finished work – the culmination of weeks, months and sometimes years of an artist’s dedication. Our own ability to understand and appreciate the time and labor taken to render this finished work, however, is in our own hands.

In regard to this understanding and appreciation, the works of English sporting artist Keith Cardnell are without a doubt in good hands. Cardnell has, in the last decade, created fewer than twelve sporting works. One patron has collected a number of these works, and recognizes them as an important part of our culture.

Early last year, Cardnell was commissioned to create a flats scene measuring a magnificent 54 inches high by 92 inches long – the artist’s largest sporting canvas ever created. Cardnell graciously brought us on the journey with him, and now we’d like to share that journey with the rest of the collecting market.

Keith Cardnell’s process is one of unyielding discipline and zero-tolerance for compromise. Every one of his works requires extensive research, profound architectural design, thorough reworking of the design to assure visual intrigue and layers upon layers of paint just to create the underpainting. Then, with painstaking detail applied over many formal stages, combined with his eye for brilliant design, mood and narrative, the magic comes to life. His highly unique style, technique, attention to detail and use of light and color crescendo to create a mood-provoking response that is as rare as any you will find in sporting art today.

As is self-evident in this commissioned piece, water is the connecting theme in all of Cardnell’s works. He does not work from a white canvas but rather “blocks in” colors to create a base image for the painting, then works from there with layer upon layer of detail work. The first stage of this magnificent flats scene consists of mapping in the large areas, and the relative size and position of the “players” in his drama – the angler and guide.

One month later, Cardnell finds himself facing what he is “pretty sure will be the most difficult and time-consuming part of the painting.” After work on the clouds and application of color to vegetation, he begins work on the furrows in the sand, which will underlay “the pin-sharp highlights.” Cardnell gives “special attention to this because (as it’s such a large area), I think it’s important to have a credible seabed that anglers will immediately relate to.”

Later that same month, as a testament to his limitless patience, Cardnell digitally renders his “production plan” – outlining each of the eight areas that “are considered separately for each pass, normally without exception and in this order.” This is Cardnell’s largest painting to date, so he has “organized it more formally than most in the past to ensure the whole canvas is considered in depth. This forces me to give each area the attention it requires to ensure no area is ‘beggared’ simply because it is proving difficult.”

About six weeks after his production plan, Cardnell’s seabed has been brought to life. In addition to tireless work on the clouds, sky and horizon line to ensure accurate perspective, the composition now has ten “roughed in” bonefish in a teardrop pattern, as well as a number of other seabed creatures and debris. Cardnell has emphasized, however, that at this stage, “whilst I’ve rendered the furthest bones indistinct, I’ve not yet distorted any of the larger fish at the bottom of the canvas or those in the middle. I think I need to wait until the paint is dry and approach this task carefully.” This attention to detail is, again, to ensure proper linear perspective and visual intrigue for the viewer.

One week later, Cardnell has just started to begin “laying out the pin-sharp seabed highlights. This is the first pass of the light bars, light refraction and light reflection off the sandy bottom creating the ‘lattice work’ of light highlights throughout the water’s surface where the light source and depth of water influence these attributes most.”

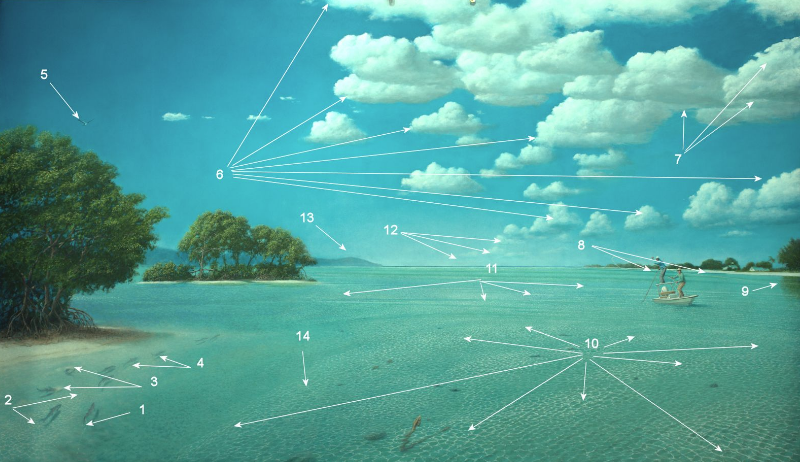

For a number of the intermediate stages of this masterpiece, Cardnell has included digital annotations to pinpoint the exact alterations made. This image is one example of just such a stage, rendered exactly two months after the previous image. This new stage includes considerable work on the sky – Cardnell notes that to most people, “a cloud is a cloud,” however, they are “fundamental to providing depth to a two-dimensional image. To the average eye, of course, the work very well could have been complete with the previous stage. Of course, these annotations proving otherwise are yet another testament to the artist’s limitless patience and dedication. While the cloud enhancements and further-sharpened highlights, among other things, enhance the linear perspective, Cardnell points out that even the smallest of details – enhancement of the Sooty Tern, for example (element five) – still contribute to the overall heavenly aura of the grand work, further drawing the viewer in to the warm waters and enticing us to discover these nuances for ourselves.

Three full days of painting after the previous image, and well over nine months after embarking on the journey, the masterpiece is complete. Cardnell points out, among other things, a few of the more drastic changes made to this seventh and final stage: “the thin-water ‘lattice’ was modified and extended for continuity;” “the sand cloud [near one of the bonefish] was enhanced and extended slightly;” and “all mid-sea to horizon areas were softened and lightened with additional small paint-strokes.” All these elements and months of dedication fuse to create a masterpiece that Cardnell is confident will provide the viewer with the opportunity for a high level of discovery – the opportunity to experience a “full visual revelation” only when viewing the work time and time again.

To explore the mind and artistic process of one of today’s top sporting art masters is quite a journey. We saw him push the limits of his abilities, and learned of the discipline he follows to achieve what he sets out to do. Cardnell has said, “I would certainly create a far greater body of work if I spent less time thinking and more time painting, but that is not how I am designed. It’s the only method through which I can get to an end result with which I am happy and for which I feel the viewer will have the best experience with my work.”

It is this deliberate refraining from execution and allowance of visual introspection that results in such magnificent paintings. Cardnell has also said he hopes his collectors “will experience pleasure in owning something I have produced and they are happy and proud to share that viewing experience with friends and family. That said, I still get a ‘buzz’ when, on someone viewing a finished painting of mine, I overhear something like, “Wow,” or “Awesome” or “Stunning.” It is a gratification that, for an instant, is far, far more thrilling than actually selling an artwork.”