The Grand Old Man of Wildlife Art

May 14, 2020

SCA Articles

SCA Articles

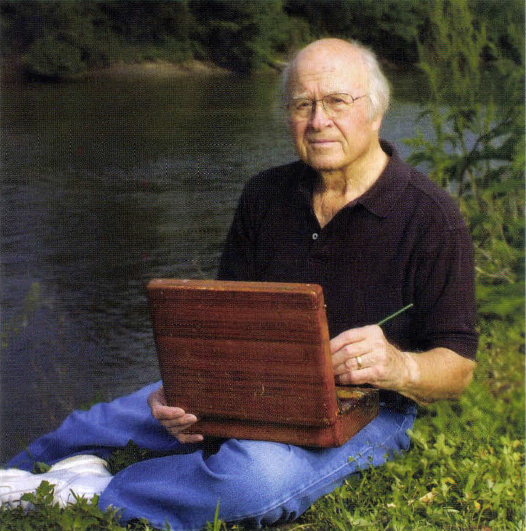

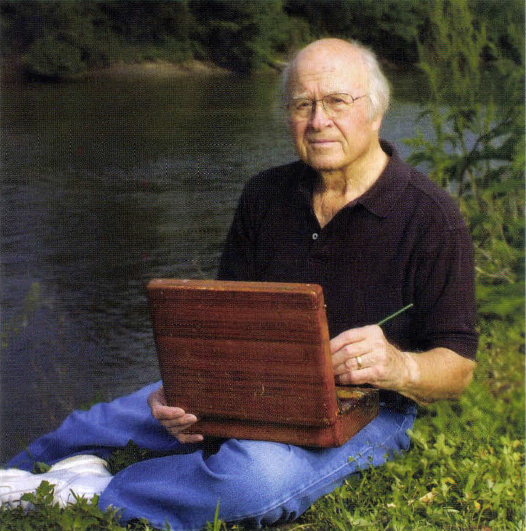

The creator of five Federal Duck Stamps and many treasured prints and originals, Maynard Reece has earned a special place in the annals of wildlife and sporting art.

Irrespective of gender, the typical American teenager is the most fashion-conscious creature on the face of the earth. This has been the case for a long time – certainly since I was a teen, which was, well, a long time ago. Your peers are judging you by what you wear, after all, and when you’re a teenager the approval of your peers means everything.

If you’ve raised a teenager – or should I say if you’ve survived a teenager – you’re nodding your head in agreement. And rolling your eyes at the memory.

In the time and place where I grew up – western Iowa in the late 1960s/early ’70s – the choice for manly headwear was a Jones-style hunting cap. You know the kind I mean: tan canvas, with a stiff brim that you fold up in back so the top edge slants down, like the wing of a paper airplane. On rainy days you can turn the brim down so it covers your ears and lets the water run off although I don’t remember any of us ever doing that.

(On second thought, Nutz Walton sometimes wore his Jones cap that way. But then, Nutz Walton was known to wear a paisley shirt with plaid pants, too.)

So why was it so cool to wear a Jones cap? Easy: Because Maynard Reece wore one, and Maynard Reece was The Man. Or at least he was if you were a teenaged Iowan who, like my buddies and me, was obsessed with waterfowl and upland bird hunting to the exclusion of just about everything else.

Well, okay, maybe not girls. Or rock-and-roll. Or beer. But that was all.

Other guys had their sports heroes; we had Maynard Reece. Forty-odd years ago, he was already a legend. (No one used the word “icon” then.) It wasn’t that we aspired to be artists; it was that we aspired to live in the world Reece painted, a world of gaudy roosters bursting from the corn and bobwhite quail boiling out of the fencerows and all the ducks we lusted after – woodies, mallards, canvasbacks – spiraling down from wind-lashed autumn skies.

In short, we wanted our lives to imitate Maynard Reece’s art.

The first Federal Duck Stamp a lot of us ever bought was his record-setting fifth, the 1971-’72 composition of cinnamon teal, two drakes and a hen poised to land, that for my money’s as good, and as compelling, as stamp art gets. It goes without saying that the design is uncommonly strong, but what elevates this stamp is how vibrantly and palpably alive its subjects are. Reece nails it in every respect: their attitude, their anatomy, their richly colorful plumage. All the elements of the cinnamon teal’s character, in other words – and he does it without resorting to fussy feather-rendering.

This is the signature of a master: the ability to convey the impression of detail without bogging down in the details themselves. Only an artist who’s on intimate terms with his subject matter can pull it off, and while I don’t know of any good way to quantify this, it’s hard to imagine a painter who’s spent more time in the field hunting, sketching and simply observing wildfowl than Maynard Reece has.

If this was true of the Maynard Reece I idolized when I was pulling my first Jones cap down on my head and slogging in to a Missouri River marsh with a sack of Carry-Lite decoys over my shoulder and a 16-gauge Model 12 under my arm, it’s undoubtedly true of the Maynard Reece who, at a spry 92, was the acknowledged Grand Old Man of wildlife art.

I caught up with Maynard years ago at the opening of Birds in Art, the flagship show of the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum in Wausau, Wisconsin. It was the 37th renewal of this internationally prestigious exhibition – and the 37th time Reece’s work has been included. Only one other artist, Guy Coheleach, shares the distinction of being in every show since the event’s inception.

Another distinction Reece shares with Coheleach is the title Master Wildlife Artist, which was bestowed on him at the 1989 Birds in Art exhibition. (Coheleach received the award in 1983.) Many of the Masters return every year for the show’s opening; among those in attendance in 2012 were such luminaries as Robert Bateman, Walter Matia and Larry Barth.

And Maynard Reece, who no one can remember not being there for a Birds in Art opening.

“Maynard’s a treasure,” says Kathy Kelsey Foley, the human dynamo who serves as the Woodson’s director. “He’s so gracious, so generous, so positive; you can’t spend any time at all around him and not come away feeling energized. He’s an inspiration, really, and what he and his work have meant to Birds in Art over the years is just incalculable.”

At 92, Maynard earned the right to sit rather than stand, and while he occupied a chair next to his panoramic depiction of a lone raven gliding over the foothills of the Rockies, I asked about his relationship with Jay “Ding” Darling, the eminent cartoonist and conservationist who influenced Reece early in his career. His blue eyes twinkled as he remembered their first meeting, in Darling’s office at the Des Moines Register.

“I was 18 years old,” Reece recalled, “so you can imagine how nervous I was. Darling had a gruff persona, and when I very timidly showed him some of my paintings, he said ‘Well, these are alright, but they’re not really going to get you anywhere. Do you want me to tell you what’s wrong with them?’

“I said ‘Yes, I want to improve,’ and Darling became my mentor. I brought my work in for him to critique for a number of years and eventually he said ‘Maynard, there’s nothing more I can teach you – but don’t stop coming by.'”

Darling’s famous farewell cartoon, published the day after his death in February 1962, depicts his studio filled with all the things that meant the most to him – including, to the right of the doorway, a painting of bobwhite quail by Maynard Reece. It was a terribly proud and poignant moment for Reece; fittingly, that painting now resides in his personal collection, having been returned to him by Darling’s heirs.

(As an aside, Reece played a prominent role in the documentary America’s Darling: J.N. “Ding” Darling, which debuted October 23 in Des Moines, Reece’s home since the 1940s.)

Of course, the most famous of Reece’s five Federal Duck Stamps – maybe the most famous Duck Stamp of all – is the 1959-’60 design featuring King Buck, the National Champion black Lab owned by John Olin, the Winchester-Western arms and ammunition magnate.

“That’s not the Duck Stamp,” Maynard said to me with a smile when I asked him about it. “That’s the ‘Buck Stamp.'”

He recalled that when he visited Olin’s Nilo Kennels in southern Illinois to watch the dog in action and make some preliminary sketches for the stamp painting, Buck’s trainer, Cotton Pershall, threw a mallard and Buck retrieved it perfectly. But when Pershall asked Buck to make a second retrieve, the dog looked at him with an expression that seemed to say You ‘re not serious, are you? and absolutely refused!

“He acted like it was beneath his dignity,” said Reece, chuckling at the memory.

It was the same when they took Buck into a room in the kennel building and posed him among his copious trophies. “He behaved like a perfect gentleman for about fifteen minutes,” according to Reece. “Then he got up and walked to the door. It was like he was telling us ‘We’re done here.’

“King Buck was a celebrity, and he knew it.”

There were other exhibition-goers waiting for their chance to chat with Maynard, so I thanked him for his time, exchanged a warm, firm handshake and moved along, marveling at all he’d done and thinking that it’s about time I got myself a new Jones cap.